We continue our look at the foundational technology and design of precision levels for surveying with an examination of the evolution of the Digital Nivellier.

There are several manufacturers of excellent digital levels. While visiting the Deutsches Optisches Museum (optics museum) in Jena to research this article, a side visit to the Zeiss campus nearby provided an opportunity to examine the history and manufacture of one of these lines of digital levels, Trimble’s DiNi® (Digital Nivellier). This is just one of many digital levels I’ve used, and they all perform well.

The DiNi manufacturing at Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH in Jena, Germany. – Photo: xyHt

Torsten Kludas, managing director of Trimble Jena GmbH, graciously gave a tour of the facilities located in the main Zeiss building and provided a history of the evolution of the various Zeiss companies. He has held various R&D and management roles within these companies for many years, having the opportunity to witness and participate in this evolution.

The history of the Zeiss companies is fascinating, including the disruption of World War II. At the war’s end, the Jena facility was essentially dismantled with U.S. and Russian forces successively taking most of the tech (and many of the engineers). The company then split between East and West Germany, development and production continued on both sides, and the company reconstituted following reunification.

From 1982 to 1988 research projects between VEB Kombinat Carl Zeiss Jena and Dresden Technical University developed automated rod reading by using a digital barcode. The first prototypes were based on the Ni-002.

By 1988, the Zeiss RENI 002A semi-automated the workflow, with optical visual observations entered and stored onboard the instrument. In 1990, WILD launched the NA2000 auto-level, the first of the new wave of digital levels on the market. In 1994, the Zeiss DiNi 10/20 was launched providing a CCD line for automated code measurement, enduring through various iterations until the present day. A deep dive into this development and testing is in the paper: “Development of Levels during the Past 25 Years, with Special Emphasis on the NI 002 Optical Geodetic Level and the DiNi Digital Level” (bit.ly/3tHLQLQ) by Matthias Menzel (Dipl.-Ing.) and Carl Zeiss of Jena GmbH.

The pioneering Zeiss Ni 002 analog level. It achieved a precision of ±0.2mm/km and is still used as a reference instrument to this day. Some early digital level prototypes were based on the Ni 002. – Photo: xyHt

The most stable place inside the main Zeiss building is where Carl Zeiss Jena and Trimble Jena have manufactured the DiNi since 1994. In a clean-room environment, 16 highly skilled workers assemble and test the instruments. Many of the team had attended one of the technical schools in Jena, or if hired from elsewhere, they undergo a one-year on-the-job training program. Like any optical instrument, collimation tests must be performed as well as calibration of the pendulum-compensator, beam splitter, and CCD. The optics are also made in-house.

“We did a lot to make production lean and with clean-room conditions,” said Kludas. “Failure rates are among the lowest in the industry.” Electronics are “aged” in environmentally controlled enclosures. Tens of thousands of units have been shipped to countries all over the world over the years—impressive numbers as digital levels are not as common in surveying firm inventories as are GNSS rovers or total stations.

Upstairs, Kludas and Trimble Jena GmbH engineer other elements found in a wide variety of surveying instruments under the Trimble Umbrella. Zeiss had changed from the grey color (Zeiss West) and orange color (Zeiss East) to blue (re-united Zeiss Geodetic Instruments), and later to yellow for Trimble developed and manufactured instruments.

Specs can be one thing, but I always look for examples of independent testing, by academia, firms, or agencies. For example, control levels for an underground rail line in New Zealand (bit.ly/48GHpj7) closed 10 km with a 4 mm residual. A leveling crew in the Pacific Northwest submitted a 20 km DiNi run to the National Geodetic Survey with a 1 mm residual (that can’t all be pure luck).

The nice thing about digital levels is that you can rough-pre-check errors along the way, avoiding most blunders and for the most part see if you will meet distance-residuals while still on site.

Torsten Kludas, Managing Director Trimble Jena GmbH poses with a selection of instruments with design input from Zeiss and Trimble. – Photo: xyHt

Another example came up in discussion at a conference with engineers working on high-speed and Maglev rail lines in China. I asked if there were any domestic manufacturers of digital levels. They said that there was no real need to; the units now on the market were of high quality, and at a good price.

One engineer related that through their own testing, they determined that the DiNi was the only unit that (at the time) met their needs for a specific phase of a high-speed rail project. And while on tour of the CERN Large Hadron Collider campus in Switzerland to interview the Large-Scale Metrology team about their geodetic infrastructure and procedures (bit.ly/3NSWRB4), an all-PhD survey crew, they related their own internal testing and at the time had settled on the DiNi.

Wayne Johnston, of Trimble surveying and mapping optical market manager, has been involved in the Trimble Jena site for the past 15 years.

“Digital levels are an important tool in the surveyor’s arsenal,” he said. “They do a specific job very well, to the extent that no practical technology has replaced it outright over the years. We’re very proud of the longevity of our DiNi for providing what our customers want in this product line; ruggedness, dependability, and above all, accuracy.”

There have been incremental improvements over the years, though some design elements have remained the same.

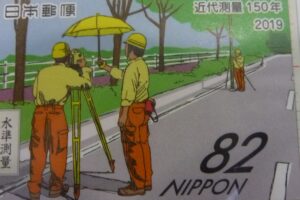

In 2019, a set of stamps commemorating the 150th anniversary of modern surveying in Japan was issued. Note the attention to detail of best practices; the use of a bipod for the invar rod, and an umbrella to keep the digital level (a DiNi) out of direct sunlight. Photo: Kludas

“You never would touch the measurement principle,” said Kludas. “Yes, in many ways it is perfect. On the one hand, it’s a relatively simple instrument. You have focus lens, you have your main objective, you have your eyepiece, you can make visual readings, and the CCD makes the rod readings. But on the other hand, things like weight balancing the vertical axis, the very precise compensator, stable optical design, and the processing—based on more than 100 years of level instrument experience.”

The display size was increased, the communication interface and other improvements were made in the software, but for the most part, the DiNi has stood the test of time since 1994.

Over the years, I have asked surveyors what additional features they would like to see on the DiNi and other digital levels. A QWERTY keyboard is a common wish list item, and/or a way to connect to an external data controller. And perhaps we might someday see smart instruments, like the smart speakers in our homes. “Hello DiNi, are you level and ready for the next observation?” But beyond that, such instruments are viewed as a reliable, consistent, very high precision, and essential tools. If a design isn’t broken, don’t fix it.