I can’t speak about other professional career paths, but I can certainly attest to land surveying after more than 40 years of “practicing” the art and science. There truly has been an opportunity to learn something new almost every day of those 40-plus years (unless I interfered). From the fundamental basics like stocking the survey rig, to tying a lath, to properly digging a hole looking for a monument, to more advanced technical skills such as setting up an instrument, keeping proper field notes, and reading plans or maps, the early years were filled with daily opportunities and challenges.

Then my learning curve began to advance into the professional skills and knowledge such as how to follow in the “footsteps,” the rules of boundary determination based on certain circumstances related to how original boundaries were created and established, case law, statute, and evidence. It is a never-ending learning opportunity, both because things change over time and because no two boundary resolutions ever seem to be exactly the same. I have grown from every one of these opportunities along the way and loved the journey.

As many as there are, countless really, a couple early on stand out in my memory as “ah ha” moments or experiences when a light of understanding was flipped on where previously there was darkness or a vacuum.

Moment #1

I took trigonometry in high school because I was expected to, and I barely passed. I mean barely. It was so abstract that I was constantly lost. The only concept I sort of got because it could be proven by regular “math” was the Pythagorean theorem. Beyond that, I couldn’t tell a cosine from a volleyball.

Fast forward to the summer after my first year of college. I was on a survey crew setting property corners for a subdivision in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. We were still using steel tapes for distances in those days, so I had learned to head-chain. As we were setting front lot corners around a cul-de-sac, I was up on a cut bank well above the instrument man. He would turn the set-out angle and get me close to line. Then he would have me hold the tape maybe a foot above the ground and look through the instrument and measure something. He would pull out his calculator, beat on the keys, then yell out, “Your add is 43” or some number between 0 and 99. The “add number” was different every time, yet I knew that every corner was the same distance from the instrument, being set up at the radius point.

After setting out all the front corners from that set-up, I came over to ask why these distances were different and what he was measuring and calculating each time. As he explained the concept of a slope distance being reduced to a horizontal distance based on the angle he was measuring each time—while drawing me a picture—it hit me. He was using the cosine of the angle he was measuring to calculate the ratio between the adjacent side (horizontal distance) and the hypotenuse (slope distance).

The light suddenly came on! There was a tangible, practical use for my demonic enemy, trigonometry! The world was right again. I took trig in college soon thereafter and wrecked the curve on every exam I took. It suddenly, in a moment on a hot summer day in the middle of a dirt road, became crystal clear to me, and almost a passion. I have embraced it ever since.

Moment #2

While working as a pack mule on the same crew doing an extensive boundary retracement, my job was to carry “stuff,” cut “stuff,” and stay out of the way. I had honed my skills in that arena well after being chewed out, I mean instructed, a few times along the way.

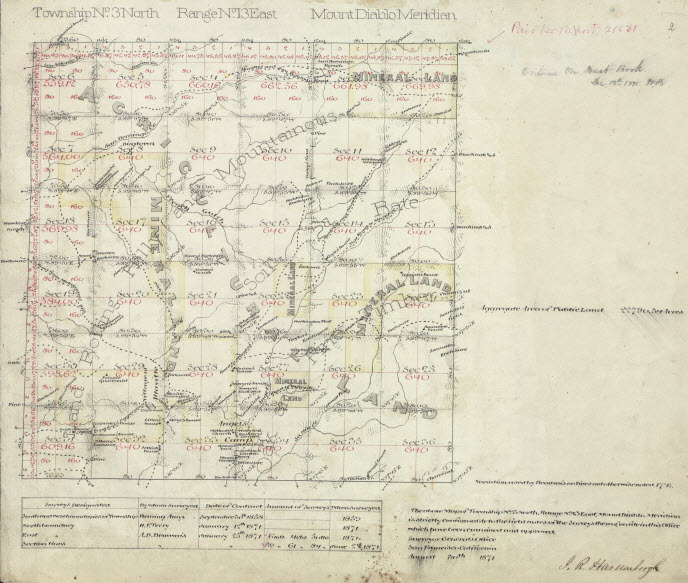

Though I didn’t know it at the time, part of what they were retracing was the original public lands survey from circa 1871 which had not been shown on a map since. I packed gear back onto a new area while the party chief and instrument man read notes, looked at maps, used compasses, and took their merry time getting to our destination. They seemed interested in every creek and ridge we crossed. I just stayed out of the way, wondering why they were “wasting time.”

We eventually got to a place where they really started looking around. Tree stumps, rocks, traces of fences. I just watched. As they scoured, one of them hollered and the other came running. I followed, carrying “stuff.” The “finder” pulled weeds back from a mound of rocks and jabbed his pocket knife into a hole in the center. The other one got down for close inspection, then pulled those old notes out again, along with his compass. They got even more excited that a couple of old tree stumps happened to be nearby, although they seemed disappointed that they were now stumps. Hey, it was stuff I wasn’t going to have to cut, was my thought. They pulled a tape out of my “stuff” bag and measured from the rocks to the stumps. The more they measured, the more excited they got. I had no clue what was going on, but one thing I did know for sure was that my two mentors were very excited about something, and that excited me.

On the hike out they explained to me what the old notes were, why they were looking at creeks, ridges, trees, and such, and I suddenly realized I had just been on the coolest treasure hunt ever! And it was successful. I was hooked on surveying that day, and the treasure hunt has always been the best part, followed by piecing together the puzzle created from the results of the hunt.

Before I wrote this article, I made a list of these moments, which was much longer than what I have shared here. Perhaps I will do a Part 2 of this topic? You see, I don’t write these “stories” for you; I write them for me, and I sure enjoy reliving them through my written words.

Seriously, I hope they have a jogged a few of your own. We all have had them. Before I am done, I hope to have more.

Credit for the top image is Griffinstorm.

This article appeared in xyHt‘s e-newsletter, Field Notes. We email it once a month, and it covers a variety of land surveying topics in a conversational tone. You’re welcome to subscribe to the e-newsletter here. (You’ll also receive the twice-monthly Pangaea newsletter with your subscription.)

This article appeared in xyHt‘s e-newsletter, Field Notes. We email it once a month, and it covers a variety of land surveying topics in a conversational tone. You’re welcome to subscribe to the e-newsletter here. (You’ll also receive the twice-monthly Pangaea newsletter with your subscription.)