Notes from a visit to the new production facility for Topcon and Sokkia optical surveying instruments.

I asked Tsutomu Ishibashi, a production line technician at Topcon’s Yamagata manufacturing facility, what message he would like to convey to the surveyors who use the products he helps produce. His answer was, “We are always trying to improve, and we are focused on quality.”

Topcon has always done that: improve and innovate. This culture and philosophy reaches business lines and societal needs beyond the surveying instruments we are familiar with. (Read more in our joint interview with Topcon president and CEO Satoshi “Steve” Hirano and Topcon Positioning Systems president and CEO Ray O’Connor.) As Ishibashi noted, there is a desire to continually improve, but sometimes external drivers force one to improve—and in a hurry.

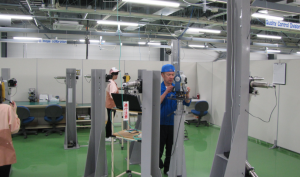

Tsutomu Ishibashi (foreground), assembly technician, performs collimation on total stations produced at the new assembly annex of the Topcon-Sokkia factory in Yamagata.

Several years ago, Topcon was facing a challenge, a good one to have but a challenge all the same. Demand was straining the legacy production capabilities for optical surveying instruments, total stations in particular. The global infrastructure boom has not seen a slowdown in demand. Legacy facilities in the Topcon Tokyo Headquarters (THQ) could not accommodate an expansion, and costs for any expanded line using legacy production processes would make it difficult to remain competitive.

The answer was to establish a completely new production line, an expansion of an existing Topcon factory in distant Yamagata Japan, and to implement multiple advances and upgrades to production processes.

Already advanced and high tech, Topcon would need to reach even higher. An easy way out of such a crunch might have driven other companies to simply create a new line in China or elsewhere, or outsource, but Hirano was not in favor of this, and for very good reasons, as we learned during our Yamagata factory tour and subsequent visit to THQ.

The New Line

Shichiro Onuma is a Topcon senior manager, and he was most closely responsible for establishing the new production line in Yamagata. Onuma joined Topcon shortly after graduating from university in Tokyo; his first duties were related to medical instrument production. His boss asked him to go overseas.

“In those days there were not many chances to speak and learn [business-level] English,” said Onuma. “Suddenly I find myself in New York. I had not studied English much before. It was a difficult time for three years but I tried to catch up.”

When Topcon introduced their first total stations to the marketplace in the early 1980’s their surveying business was growing rapidly, so Onuma transferred to the survey group. Then the chief of that group “Bob” Iguchi sent him all over the U.S. to distributors, conventions, and surveying training at a reseller (Portland Precision Instruments in Kent Washington). He said that it was “a tough time, but a good opportunity.” (Iguchi was later the senior managing executive officer of Topcon Corporation and played a key role in forming the new Topcon Laser Systems company in California in 1994 that became Topcon Positioning Systems, now helmed by Ray O’Connor.)

When Onuma returned to Japan, his duties increased in the surveying sector; he and the company learned a lot about moving production lines with the merger of Topcon and Sokkia when the lines were moved from the former Sokkia facility in Kanagawa (west of Tokyo) to THQ. He also spent a year setting up a new manufacturing facility in China for a limited selection of products.“We make a basic model total station in this facility, which is sold primarily in China, that is of superior quality to their domestically designed instruments,” Onuma said.

There are limited numbers of components made outside of Japan, like the TSshield (security and asset tracking telematics device put in the total stations) that is produced by their joint venture company, Tierra, in Turin, Italy, but when it comes to total stations the desire is domestic production. For one reason, Onuma said, “[president] Hirano loves to make the most sophisticated instruments in Japan—he wants Japanese quality.”

A second reason is that Japan is the cornucopia of high-tech component manufacturers, large and small, that can easily meet all specifications and expectations.

And lastly, the proposed move to a new facility would also involve very bold moves and production process design changes that would best be met with the existing team at hand. Topcon made the same decision for its GNSS manufacturing facility in Livermore, California; domestic production was penciled out as more cost-effective and with higher quality than outsourcing. Onuma was handed the task of creating the new line in Yamagata with an ambitious timeline attached.

“We began design in August of 2016 and broke ground in January of 2017. The factory expansion was complete in July of 2017,” said Onuma. “We were up and running within a few weeks.”

Topcon’s Yamagata factory front entrance (left) and new addition for total station production (right). Also produced at this factory are medical instruments (upstairs in an environmentally controlled workspace) that include eye care retina cameras and optical tomography instruments. Above photo, from left to right Kusano, Takahashi, Onuma, Schrock, and Nakamura

In the period of six months following the launch, production increased by 150%.

I asked if there were any major hiccups or challenges, and Onuma said, “I was lucky. But we had a lot of experience with the merged Sokkia factory, then setting up one line in China. We were confident in our design and production team.”

Topcon has had a presence in Yamagata since 1946. Elements of manufacturing had been decentralized to the remoter areas of Japan during the war, and even today Topcon likes having an alternate HQ should there be any problems in Tokyo such as natural disasters. An old factory is northwest of the city where various instruments had been manufactured over the decades and a newer facility that I visited. (The newer one had the addition constructed in 2017 with more parking for the more-than 90 additional staff.)

Yamagata City is relatively new, having been established in the late 19th century; the city has a population of about 250,000. There are, though, very old smaller communities, feudal castles, and hot springs scattered about a prefecture (state) of the same name. The origin of the name is unclear, but it roughly means, “mountain place” as it is ringed by beautiful mountains. This is off the beaten path as far as tourism goes, but is a very pleasant place to work and live, and the local cuisine alone might be worth a visit. Topcon transferred about 60 staff from THQ for the new line and hired about 40 more locally.

From the outside, this new facility (and expansion on the east side of the existing Topcon factories) is an unassuming but visually appealing single-story white box: 100m long and 30m wide. This is the newest of the surveying instrument factories I have visited in recent years and I expected the latest in tools and equipment, but in terms of high-tech manufacturing and finely-honed production processes what I saw inside during the tour was nothing short of astounding.

History

In 1873, 13-year-old Kintaro Hattori had begun an apprenticeship in clock making in Edo Era in Tokyo. This was a pivotal time in Japan; the three-century-long Shogun Era had just ended, and Japan had opened to the West. Japan’s long history of high precision and detail in manufacturing, art, metallurgy, and ceramics was a splendid fit for adapting technology from the West and fostering further innovation.

After his first postings with clock makers, young Kintaro returned home to what is now the present-day Ginza District of Tokyo and posted a sign outside his house: “Hattori Clock Repair.” K. Hattori & Co. (now Seiko Holdings) was born.

On the site of an early headquarters Hattori constructed a clock tower, now known as the Seiko Clock Tower, recognized as the iconic heart of the Ginza and one of the most recognizable landmarks in Tokyo and Japan.

On the site of an early headquarters Hattori constructed a clock tower, now known as the Seiko Clock Tower, recognized as the iconic heart of the Ginza and one of the most recognizable landmarks in Tokyo and Japan.

Among the divisions of this pioneering clock, watch, and technology company was one that manufactured optical surveying instruments. In 1932, Hattori chose one of his sons in law to become the first president of this division, established as Tokyo Optical Co.—later to become Topcon.

A year later, a new factory was built in Itabashi-Ku, a district in the north end of the present-day Tokyo megalopolis, the same location as the current THQ. In 1946 the Yamagata manufacturing facility was established. Surveying instruments to date had been mainly produced for military purposes, but in 1947 Tokyo Optical embarked on first serving a growing market for medical optical devices, specifically for eye-care.

Topcon’s first total station was the 1980 GTS-1 “Guppy” theodolite incorporating an EDM. This instrument and those soon to follow created brand recognition among surveyors worldwide, had a tremendous impact on the industry, and drove Topcon’s future in surveying instrumentation.

In the early 1950s, the name “Topcon” first appeared as a line of cameras produced by the company, which gained a reputation as excellent press cameras, with the U.S. Department of Defense as a major client. The Topcon RE Super was the first single-lens reflex camera with a full aperture metering system. By the late 1950s, the company was back in production with surveying instruments for all markets.

In 1989 the name “Topcon Corporation” was officially adopted, and in 1994 Topcon Laser Systems Inc (Now Topcon Positioning Systems) was established in California. The 2008 merger with Sokkia further bolstered the surveying instrumentation arm of the company.

Presently, Topcon operates in three functional groups: Medical (eye care), Smart Infrastructure (surveying and scanning), and Positioning (agriculture and construction).

The First 100 Meters

The production floor is 30m wide, with a 10m-wide section on one side where parts are aggregated and the production engineering team, procurement, and production teams work. There are no partitions in this open-office configuration, just desks clustered together. I can say from experience doing a work study in Japan that an open layout tends to boost productivity and discourages folks from distractions. On the other 20m side are several assembly lines perpendicular to the building axis.

Several short assembly lines run across the production floor, with environmental testing and curing chambers at the other end. Instruments are tested at temperature ranges from at the other end. Instruments are tested at temperature ranges from -30’C to + 70’C.

The largest share of the floor space is occupied by testing stations. There are tests at every assembly step, environmental chamber tests at the end of each short assembly line, collimation, and EDM tests on several long interferometry tracks. Finally, the fully assembled total stations undergo tests emulating normal operations by an independent QA/QC team in a separate area. Onuma said that team is made up of local Yamagata hires who are very fast at operating the instruments—they would probably be amazing to have on a survey crew.

An independent QA/QC team performs further tests on completed instruments prior to shipping.

My guide for the tour was Onuma-san, and we were joined by floor manager Juji Kusano. On large display screens between the assembly and engineering areas was the environmental monitoring status. Optimal for production would be a dust free location, controlled humidity, and a temperature range not varying by more than one degree (Celsius). The floor was specially designed to remain stable and eliminate vibration. GNSS receivers on the roof provide precise time to synchronize the network and systems in the factory. Currently, they are working on stabilizing the temperature, which is difficult because the environmental test chambers can emit a lot of heat, and the range sometimes is 2 degrees. Another display is of the production flow, with every instrument tracked by serial number. One display shows where each instrument is ordered and delivered worldwide.

More than a dozen different instruments in the Topcon and Sokkia lines are built there, and orders can vary on what features are desired, even with regional differences. The global orders are ingested and programmed into the production schedule, and parts are staged accordingly. While no one is allowed to give exact numbers, it is safe to say that thousands are produced on that single 3,000 square-meter factory floor every work day. One goal of the production planning is to even out the workflow to be able to meet order surges without excessive overtime.

Topcon senior manager, Shichiro Onuma, demonstrates a computer-controlled torque driver.

Every instrument has a unique serial number that is assigned at the very first assembly station, in this case when the main axis is attached to the base. Onuma and Kusano demonstrated a torque drive controlled by a computer and an applicator and adhesive—also computer-controlled.

Why not fully automate? There is a fine line, a balance between the decision-making skills of the human operator and the precise control that the computer can provide. Through finding this balance and designing new workflows, Topcon has been able to greatly increase productivity and has the capacity to meet increasing demands.

On the Line

Tsutomu Ishibashi performs collimation for total station on the new production line at the Yamegate factory. Note that he wears his hat backwards, just like a field surveyors, so the bill does not get in the way while looking through the instrument eyepiece.

At one of the collimation stations along the production line for total stations at the Topcon Yamagata factory, I spoke with Tsutomu Ishibashi, a bright and affable young fellow who has been working at Topcon for more than a decade.

Ishibashi transferred from the Tokyo facility when the new production line for total stations was established at the Yamagata facility in July of 2017. He says that he enjoys working in the new facility and finds Yamagata to be nice place to live, although it might take time to adjust to the winters that are much colder than in Tokyo.

On the working environment, Ishibashi says, “The workers talk to each other; we look at how things are done, and we are always trying to come up with new ways to improve.”

I asked what he has learned about the work surveyors do with the instruments he helps produce, and he said he is understanding more and more the importance of what surveyors do, and the company does demonstrations for the staff.

True to the image of a Japanese factory, the day starts with morning exercise. There is an excellent canteen, and the employees participate in group activities ranging from a baseball team, beer parties, and the annual “ohana-mi” (cherry blossom viewing).

Topcon has had strong presence in Yamagata for more than 70 years, and when they post positions there is a lot of interest from local applicants. Unlike the Tokyo facility, where public transportation is often the only practical option, most Yamagata employees drive to work. Production workers are mostly trained on the job. The company seeks applicants even fresh from high school; good health and good academics are a plus.

Topcon requires that employees continue to improve their skills, and some seek national certifications in, for example, electronics and machining. These involve a lot of self-study, but also instruction from others in the company. Offsite classes and certifications often involve a visit from an evaluator.

The newly updated production line for total stations, built from scratch in Yamagata in 2017, provided an opportunity to rethink processes and workflows and to find the right balance between automation and manual tasks. Production process design considerations included reducing tedium for the workers, and there are opportunities to learn and work in different functions.

The Handle

An assembly technician uses Bluetooth-enabled torque drivers to adjust casings on the telescope assembly and main body of the station.

A finished total station is perhaps one of the most sophisticated instruments manufactured for sometimes harsh environments and rough handling by users. Everything has to fit perfectly. Die casting and machining is mostly handled by another Topcon facility in nearby Tamura, Fukushima, with metrology bench measurements verifying specifications stated in microns. Some optics and polished glass are provided by subsidiary Optonexus.

Even when parts are manufactured by contracted firms, Topcon will often manufacture jigs and provide these for verification of compliance before they leave the other factories.

Fitting parts together without inducing stress during assembly requires the use of calibrated tools like torque drivers, but Topcon has added a new twist (no pun intended) by adding Bluetooth handles to torque drivers. Every action is recorded, and the driver is tracked for preventative calibration at least monthly. Action logs are connected to each instrument’s serial number as well as to the badge number of each employee assembling, inspecting, testing, or shipping the final product.

One of the interferometer tracks (right) is 45m long with the target carriage fondly referred to as the “shinkansen” (above). It robotically runs a preprogrammed series of tests at different distances for each instrument. Other, shorter interferometers are utilized for different tests (to left of the main track).

What Color Is that Case?

After exhaustive testing—and with every assembly step, part, and test in a database that can follow the instrument throughout its life—the final step is shipping. True to the production goals of eliminating any chance of human error, even the packaging and shipping process is tightly controlled and tracked. With multiple models being shipped and under both the Topcon and Sokkia brands, not to mention varied accessory packages, there might have been a chance (in a legacy analog shipping environment) for errors. But not here.

When an individual instrument’s serial number is scanned, the database is accessed and the bins for the corresponding accessories light up. The shipping technician pulls the part and scans its barcode and their own badge and then places these in the case—only then does the light go out. To be sure there is no dispute between a distributor and the factory on what was or was not in the case, a photo is taken before the case is closed. And, to be sure that a Topcon instrument was not put in a Sokkia case and vice versa, another camera verifies the case color.

The accessory list for each instrument is accessed by a database and lights up parts bins for the technician to gather and place in the case; a camera records what is in the case before shipping.

The day’s finished instruments are marshaled at the south entrance of the floor for loading into the delivery trucks that arrive between 3:00 and 5:00 pm.

The first 100 meters in the life of your instrument undergo a lifetime of measurement in a single day, and you can be confident that some the finest surveying instruments have passed through the doors of this factory.

Topcon Headquarters, Tokyo

“THQ” stands on the site of the original Tokyo Optical Co. factory in the surprisingly quiet Itabashi district just north of central Tokyo. The factory has had a few facelifts, and a modern office section lines the entrance driveway. In the lobby is a mini-museum of Topcon and Sokkia instruments (a great stop for surveyors visiting Tokyo) and eye care medical instruments.

Nostalgia was sparked for me when I got to see several models of Topcon’s “Guppy”; this was the first total station I got to use—mechanical but with a built-in EDM. Like many in surveying, this first generation of total stations (and similar models) totally changed the way we surveyed. For me the immediate change was in being able to pack this light-weight system through the Alaska tundra and avoid extra hours (and days) of chaining, as well as avoiding having to lug a separate theodolite around and one of the giant EDMs of the day.

A group of college students visits the company mission exhibit at the Topcon headquarters in Tokyo. Interactive displays emphasize the three functional divisions of Topcon: Smart infrastructure. Positioning, and Medical.

There is also a new interactive display area adjacent to the lobby that, on the day of my visit, was hosting a large group of college students—potential future employees. The brainchild of president Hirano, the displays include dioramas, instruments in use, and augmented reality elements you can view on handheld tablets.

Hirano, in an interview later that day, stated that he did not just want to have a showroom of new instruments; he was not aiming the displays at customers or for sales. Instead he wanted to show all of the industries that Topcon’s products and solutions support. There are medical displays, agriculture, construction, surveying, mapping, and more. These show stakeholders and especially employees that their work serves greater societal needs. Years ago, Hirano asked people in Topcon what they knew of the company and what the company did, and the responses were often quite limited to the market segments they worked in; he wanted to change that.

Although the production lines for total stations were moved to Yamagata, THQ continues to manufacture other products; these include laser scanners and pipe lasers. But THQ also provides essential support for total-station development and production, namely research and development and quality assurance.

Research and Development

Kaoru Kumagai is a Topcon executive officer and vice general manager of the product development division based at THQ. “My first product was the GTS [Guppy], and I was doing the PC boards, designing them by hand,” Kumagai said. “Today this would be done with CAD. When we did our first laser product with Steve [Hirano], this was a first day of school for all of us. There were no people to ask, we had to learn from scratch.” I was pleased to tell Kumagai that the Guppy was my first total station and it completely changed the way me and my crew worked.

But much has changed. The product lines are mature, and now the team at Topcon has a deep bench of experts in many fields.

For an example of how the R&D process works in a product familiar to surveyors, I asked about the ultra sonic motor in the GT total station released two years ago. Kumagai told the story. “For more than 20 years we have made robotic total stations. All companies were using gear heads—lots of parts and wear and tear,” Kumagai said.

Japan is the home of many world-class elector-mechanical developers and manufacturers. “We were in communication with domestic companies that make a lot of different types of motors,” Kumagai said. “From my searching, ultra sonic worked best in direct comparison. But our needs were different for other customers—achieving high accuracy control is very difficult. Ultra sonic has the advantage of speed; most total stations are slow. We want speed, but we have to control to a few micro radians, so it was a special request.”

Kumagai’;s team was successful, and the result was the ultra sonic motor in the GT; this met his goals of faster, with fewer parts to wear out. Kumagai said that the overall philosophy of his team is to develop world-class products.

Sokkia

Sokkia total stations are manufactured on the same production line as Topcon instruments at the Yamagata factory. Production line manager Juji Kusano looks on as a Sokkia CX-60 Compact X-cellence Station is cleaned and checked before interferometry tests.

In 2008, Sokkia merged with Topcon to form one of the most prominent providers of surveying instruments and solutions. Already a global leader, Sokkia brought to this merger almost 90 years of experience in the industry, unique manufacturing and design innovation, name recognition, a global distribution chain, and a solid reputation for precision and reliability. As many of the people interviewed for this article reiterated, it has been in the best interests of Topcon to maintain Sokkia as its own product line and distribution channel.

Sokkia was established in 1920 as Sokkisha, a producer of surveying and other measurement instruments. In the late 1940s the Lietz company (not to be confused with Leitz) became a distributor for Sokkisha, making the name familiar to the North American market. Lietz was later acquired by Sokkisha, and the company further expanded in Europe and Australasia.

In 1990, 70 years after the founding of the company, the name changed to Sokkia. They produced many industry-leading products, like the popular legacy SET series, and many first-in-the-industry innovations, including today.

As Topcon Positioning Systems president, Ray O’Connor, noted in an interview for this article, “There was a time when Sokkia and [only one other brand] had a half-second total station. And look at the little “bullet” GNSS rover,” referring to the unique and compact GNSS receiver with a helical antenna.

Satoshi Hirano, Topcon president and CEO, said in the same interview that there are now common elements shared by Sokkia and Topcon instruments, like in some of the die-cast and machined chassis. “There are car manufacturers that do the same thing, like Volkswagen with Porsche and Audi. The Topcon and Sokkia R&D are the same group, with unique features developed separately.”

Sokkia total stations are produced on the same new assembly line at the Yamagata facility, including the flagship Sokkia iX and SX series total stations. Software from the popular SDR lineage continues with SDR4000 (particularly popular in Japan) and SiteHunter (popular in Europe). I remember well using Sokkisha instruments and the groundbreaking SDR33 software back in the day.

Expertise on precision manufacturing from Sokkia that the merger brought has greatly contributed to the whole. There have been other advantages from the merger and in keeping the separate brand. O’Connor said, “We did not want to dilute the business we purchased. Because Sokkia had its own revenue worldwide and in some markets has dominant market share, and if you bundle it into one brand—you might lose that.”

Quality Control

Hiroyuki Nishizawa is the executive officer and general manager of the quality assurance division of Topcon. I had always wondered how manufacturers achieve those IP ratings we see on product brochures, so Nishizawa gave me a tour of the test chambers and contraptions used to push product designs to their limits.

Typically, on surveying instruments we see ratings of IP65, IP66, or IP67. The IP means “ingress protection” or “international protection” (you’d think industries could settle on one definition). The first digit, 6, is z rating for dust. The second is for water; 5 is for water from low pressure jets, 6 is for high pressure jets, 7 is for full submersion for short periods, and 8 for long periods.

A Topcon GT in the inundation test chamber (below). Nishizawa Q.A. general manager and QA team at the vibration table (above).

The first test station was for water resistance ratings. A Topcon GT was inside going through, the body rotating as well as with action of the scope. We got to blast it with jets from all angles, even underneath—up to 12.5 liters per minute for an IP65 rating. The water flow was so heavy that the windshield wiper on the chamber window could not keep up. Next was the dust chamber, with specially ground stone “mine dust” dust blown in from all directions.

But there are tests that do not have specific external ratings, such as vibration. Topcon wants to make sure its products can withstand jolts and vibration, not only on the job but also in shipping and handling. The QA team uses several shake tables to simulate conditions that might be encountered during shipping by truck, rail, sea, or air. The vibration of aircraft can be high from resonance from the engines and air passing over the fuselage and wings. Instruments get shake and vibration tests in and out of cases, in padded shipping boxes and out, restrained and unrestrained.

Product designs are tested prior to being put into full production and in post-production if there are any design changes or modifications.

Getting to Know Your Instruments

The instruments we use in surveying, mapping, and construction are sophisticated, and innovation is relentless. We use these instruments in harsh conditions and expect a lot from them, but we pay a lot for them. We hope that these glimpses into the manufacturer of your instruments demystify them and foster a bit of kinship with the people who design and build them for you.

There is a wide range of instrumentation out there. On one end are cobbled-together systems playing the price game, and on the other end are mature and finely crafted instruments, like the clocks and watches that K. Hattori made by hand over a century ago. It is fair to say that Topcon and Sokkia instruments solidly fit in the latter category.