You can now use point clouds and massive geospatial data with GIS through the web and your desktop with new software.

Above: London rendered in 3D with London Underground data.

For years, point clouds (lidar, laserscan, and multibeam) have been pretty useless to GIS users. When a GIS user had to analyze the data, often the data would get converted to some useless 2D raster that would then have to be (poorly) analyzed in a 2D interface for 3D issues. Is it time to get excited about the ArcGIS Pro?

Survey and GIS Have Not Mixed

In a typical project lifecycle, surveyed data is used at every stage, from preplanning to planning, then to inception and on to operation and maintenance. So too is the GIS, as analysis is required of the geographic risks and issues relating to the build throughout the project. But, the two disciplines rarely meet.

Over the past 15 years, as I’ve worked on numerous projects, the only time I’ve had to analyze survey data has been within a 2D GIS environment or when converting a high-quality point cloud into a raster that could be used on a web map.

It is for this reason, in part, that a gap has grown between survey and GIS, with many survey companies preferring to use technical drawing software such as AutoCAD.

As Eric Gakstatter states in his blog on Geospatial Solutions,

“After nearly 25 years in the GPS/GNSS and GIS industries, data mismatch (“my data doesn’t line up”) is still the #1 question I get from people. The problem is two-fold.

1. People, even educated geospatial professionals, have a general lack of understanding of the different horizontal datums being used (not to mention vertical datums).

2. Software vendors (even the major ones) have generally done a poor job of keeping up with modern datum transformations. While most software makes it easy to transform data from one horizontal datum to another, they mostly do it wrong.”

So, what if I told you that there was a way for the GIS user to use surveyed point clouds throughout the project lifecycle and quickly and accurately render it both on his or her desktop and a 3D web map–alongside other geospatial data, like risks, issues, and topography?

What if I then told you that the software also handled vertical datum transformations?

A year ago I would have been shunned as an idiot if I had made the above suggestion, but now this is not only possible but extremely easy.

Esri Brought Their “A Game”

Over the last few months I have been using point clouds from a company called 3D Laser Mapping, based in Nottingham, UK, to demonstrate their high-precision laserscan data through web maps, some data as large as 30GB. Here’s how I’ve been successful with it.

I am “software agnostic” so that my clients get the right solution for their needs, and quite often their needs span the entire project lifecycle. This is where the Esri solution, ArcGIS Pro, comes in. Esri has underplayed its replacement for the old creaky ArcGIS Desktop; when you look under the bonnet of ArcGIS Pro, you have to stand back to really comprehend how advanced this GIS is.

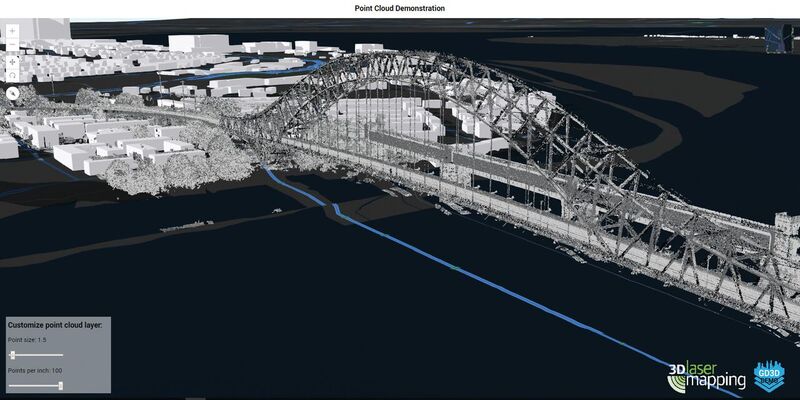

The Jubilee Bridge near Runcorn, UK, captured using the ROBIN mobile laser scanner from 3D Laser Mapping and 3D vector buildings added for analysis.

For years we have been able to use lidar data within software, but we’ve had many questions over the use of the Esri Proprietary Format. It looks like this new software answers many of those questions as it efficiently renders point clouds within the 3D GIS scenes.

Furthermore, by converting the point cloud to the Esri Scene Layer Packet (slpk) format, the software then uses a method similar to a quad tree structure on the data so that it can render amazingly fast.

Because 3D data is more power-intensive, many 3D web companies have developed methods for rendering massive models through the web. Esri’s method is called i3s, which is similar to the quadtree and octree method whereby data is reduced to levels of detail so that only the required data is called up. (See H. Samet and R. Webbers’ original paper on storing polygons using quatrees from 1985).

A point cloud of Nottingham, UK captured using the ROBIN mobile laser scanner from 3D Laser Mapping and 3D vector buildings added for analysis.

With pointclouds, multipatches, polylines, and other data in the slpk format, it’s possible to render massive data such as all the buildings in London, fully attributed, through a web interface using your mobile phone. More importantly for the surveyor and GIS analyst, it allows for giant point clouds to be rendered not only through a desktop but also through a web browser.

This can be leveraged even further by using Esri’s javascript API (4.3) that allows interactive sliders, which enable the user to adjust the points per inch and point size. In the example at top, left, you can see that I am rendering 100 points per inch!

High-resolution point cloud injected with RGB values of a Breakwater in Scotland, captured to monitor scour and erosion. Data from Niras Fraenkel.

The visualization provided by the ArcGIS online 3D web viewers (the Esri 3D web map format) allows for rendering these massive models both above and below sea level, thus adding the ability to visualize underground detail, offshore assets, and even the London Underground.

It’s All about the Datum

All of the above would be useless if it weren’t for the horizontal and vertical coordinate systems to support it, and I have great pleasure in telling you that I emailed Esri about this the second I started working with point clouds on this platform.

Their answer? Not only have they employed all the horizontal datum transformations, but they have also implemented a lot of the vertical transformations in ArcGIS Pro 1.4 (according to Melita Kennedy, Esri product manager).

Looking through the huge list of coordinate systems and transformations, I can tell that a lot of work has been done to ensure that ArcGIS Pro is as current as possible. At the time of writing, I can see the latest OSTN15 transformation, which was released only six months ago.

Let’s Not Get too Excited

This all sounds too good to be true: a software that can handle your GML data, DWG data, point cloud data, 3D models, and GIS data–and also render it all on the web for project-wide collaboration. Well, ArcGIS Pro does it and it does it well. Furthermore, in the pipeline are plans for it to handle stereo imagery, WFS format, and live streaming data.

Unfortunately, it does have a few drawbacks. Yes, it does handle enormous point clouds and massive 3D models, but to get them into the super-quick slpk format you need to bring them into the desktop to verify them and convert them. As you would expect, this is very intense on the computer; if you haven’t got a gaming PC with a fair bit of RAM, then your machine will use all its resources.

Underground data can be navigated properly only in a “local scene.” This is a web map that uses a projected coordinate system (hence, local). It worked well when I tried, although it struggled to navigate around some data that was 800m below sea level. After I asked Esri about it, the developers said that they were aware and already looking into it.

The web viewers don’t handle data from multiple coordinate systems, meaning that if you want to create a web map with offshore data in one coordinate system, you cannot mix it with the onshore data that’s in a different coordinate system.

Being able to take raw point clouds into a GIS and serve them up on the internet rapidly could save companies huge amounts of money.

Also, to make it all a little trickier, if you need one of the Esri basemaps in your web map, then your data needs to be in either WGS84 (EPSG 4326) or Web Mercator (Auxillary Sphere) (EPSG 3857).

Some people may argue that it’s good practice to ensure that your project is all captured in the same coordinate system, although in reality this is never the case, with CAD users creating local grids, offshore surveyors needing to alter the parameters to ensure a more accurate capture, and that inevitable person who didnÕt read the survey specification.

My last tiny niggle is that this tool is developing quickly. I’ve used it from the first release, so I’m getting a little lost in the frequent updates and upgrades that occur on a three-month lifecycle. You might find yourself contacting Esri about a problem only to find that a new tool has been developed that you hadnÕt spotted or been made aware of.

To put this rapid change into context, the update from version 1.3 to 1.4 included almost 20 new features, not to mention the huge list of bug fixes and updates to the current tool sets. At times, the software can feel like a beta release even though it is a fully functioning Death Star.

First Point of Call

Although not quite perfect, Arc- GIS Pro has the capability to become the first port of call for all industries that use survey data and GIS in their workflows. Being able to take raw point clouds into a GIS and serve them up on the internet rapidly–alongside geospatial data about risks, issues, and constraints–could save companies huge amounts of money as well as reduce the response time for critical and rapid response providers.

When it comes to using point clouds or massive city data, there’s not another GIS that can come close to providing data in this manner. In fact, itÕs hard to think of non-geospatial software that can provide such large data in such an efficient manner, both on the desktop and through a web map or visualization.