As GISCorps celebrates two decades of voluntary map-making missions, we learn from their volunteers how sharing one’s GIS skills where they are needed can be a force for good.

Holly Torpey collecting GIS data in the field. “Volunteering at GISCorps exposes one to people, organizations, and GIS use cases that you might never otherwise encounter.”

It was during the heyday of Afghanistan’s peace-time reconstruction, after many years of destructive conflicts, that Shoreh Elhami found herself teaching GIS in Kabul in 2005. Her work there, which was part of a capacity-building mission backed by the United Nations Development Program, was to support the mapping activities of the Afghanistan Information Management Services (AIMS), a local organization. Specifically, AIMS wanted to improve its geographic information system capabilities by moving from ArcView to ArcGIS.

“AIMS had relocated from Pakistan to Afghanistan and was in need of GIS support,” says Elhami. “At that time, I was an authorized ArcGIS instructor, so I taught the AIMS team how to use ArcGIS.”

Elhami, who has an architectural engineering degree from Iran and a Master’s in City and Regional Planning from the Ohio State University, now works for the City of Columbus as the City’s Data and Analytics lead. She is also the founder of GISCorps, an organization that coordinates short-term volunteer GIS services worldwide to communities in need.

GISCorps is a program of URISA (Urban and Regional Information Systems Association), a non-profit association made up of GIS professionals and experts in geospatial technologies. URISA provides various activities that contribute to the advancement of the GIS profession, including conferences, seminars, and trainings, and has several chapters in the U.S., Canada, and the Caribbean. Yet while URISA was incorporated way back in 1966, it was only in 2003 that a volunteer program within the organization was established.

“I wondered whether GIS professionals would be willing to volunteer their expertise to serve communities in need,” recalls Elhami. “It was a question that has been in my head since 2001.”

Katie Picchione working at FEMA prior to volunteering. “I joined GISCorps so I could continue supporting a mission that’s very important to me.”

Elhami shared her GIS-volunteering idea with a few colleagues during the URISA conference held that same year in Long Beach, California. And to her surprise, everyone who she spoke with reacted positively, even encouraging her to form a team.

“The idea of giving back and doing GIS for good by using your GIS skills caught on very rapidly and enthusiastically by both URISA and other GIS colleagues at large,” she says.

Inspired by the initial support that she got, Elhami posted an online form to allow people to register as volunteers. “I signed up as the first volunteer and then several other colleagues followed after,” said Elhami. “At the time of endorsement by URISA in October 2003, we already had 41 volunteers in our database.”

Her voluntary work in Afghanistan is one of the many missions that Elhami has undertaken with GISCorps, and it still leaves her with fond memories.

“I wanted to learn what it was like to work at a location and understand how hard it would be,” she says. The organization has since sent six more volunteers to Kabul, although deploying additional volunteers has ceased due to the country’s current security situation.

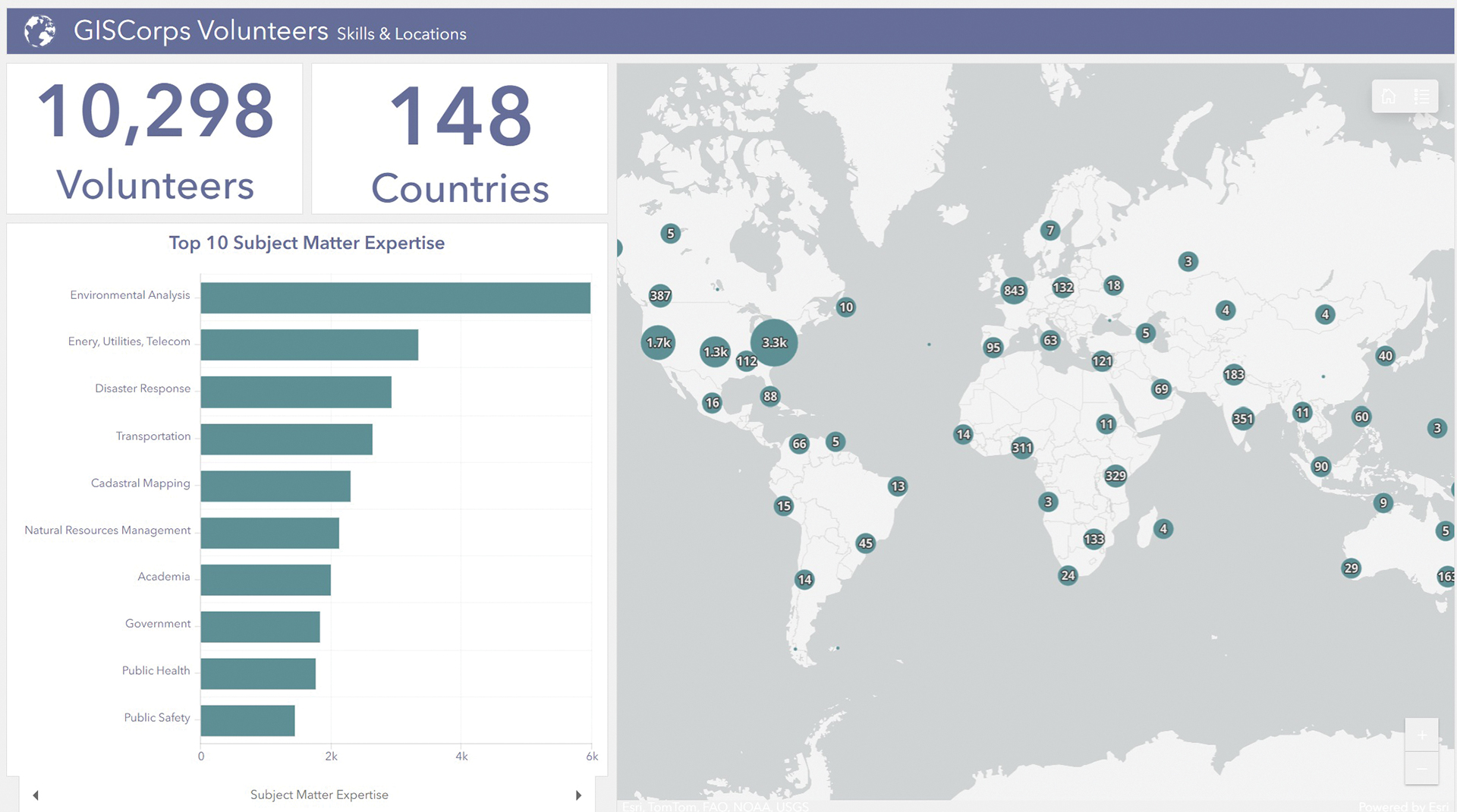

Two decades on, and despite many other challenges, GISCorps has now grown to more than 10,000 volunteers who come not just from the U.S. and Canada, but also from more than 140 countries, including the U.K., India, and Australia. To help manage its activities, the organization has a 10-member, all-volunteer Core Committee, plus a program coordinator who works part time. They also have an advisory board which offers its expertise and advice.

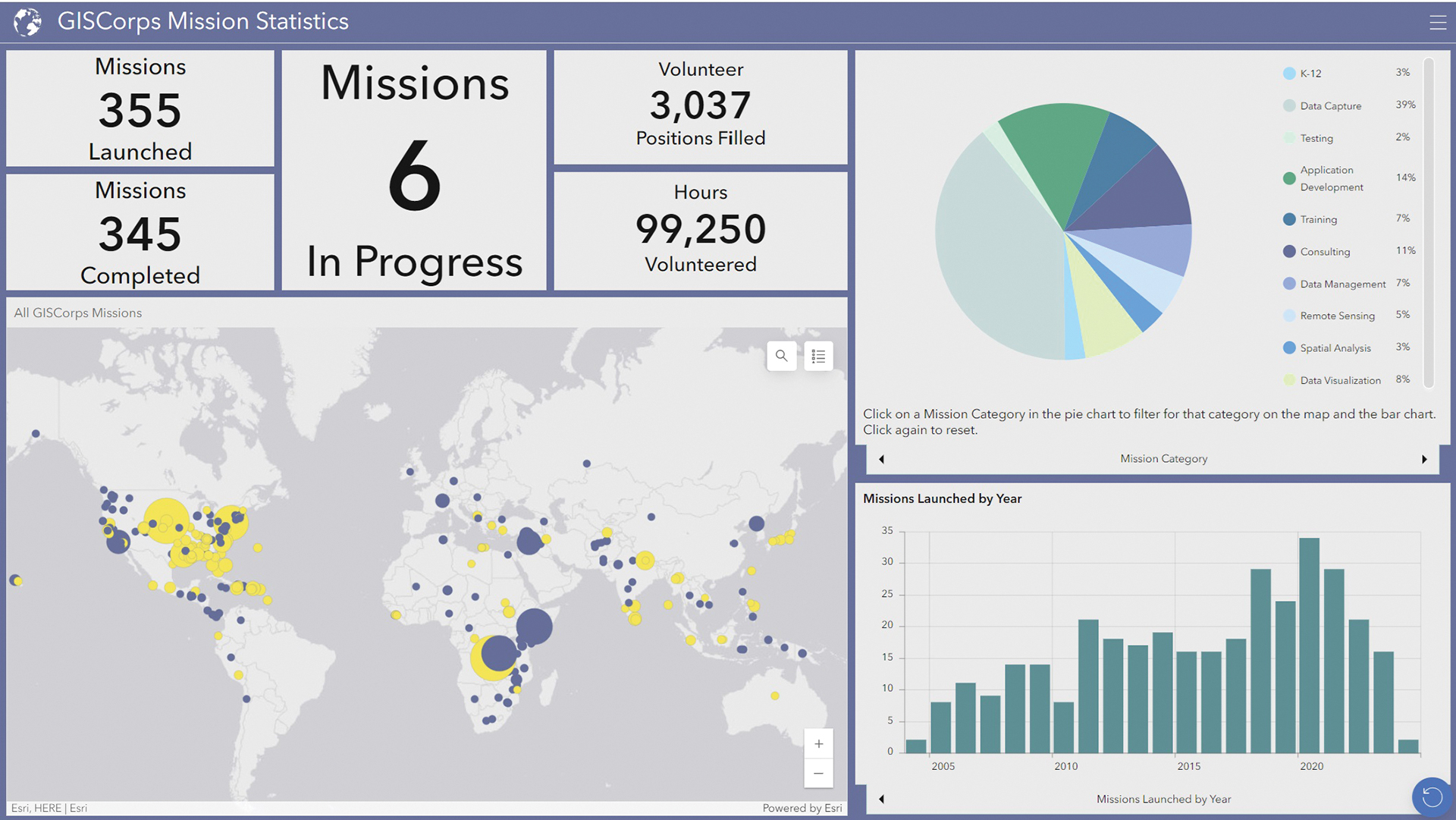

”We have launched 355 projects in 84 countries throughout the years, with participation by more than 3,000 of our volunteers,” says Elhami. “That’s approximately 100,000 volunteer hours to date.”

Many hands make light work

GISCorps founder, Shoreh Elhami, teaching GIS in Kabul, Afghanistan. “The idea of doing GIS for good caught on very rapidly.”

Holly Torpey and Katie Picchione are two of those people who volunteer with GISCorps. Both women are involved in the organization’s PhotoMappers project, a crowdsourcing effort where volunteers find photos posted to social media in the first 24 to 48 hours after a disaster, figure out where those photos were taken, and upload them to a web map.

“This data is useful to federal, state, and volunteer emergency managers who often have little other imagery available during that period,” says Picchione. And depending on the scale of the disaster, GISCorps mobilizes a team of around 10 to 30 volunteers to help sort out and geolocate the images.

“The PhotoMappers project provides a unique alternative source of information to verify and fill information gaps during these incidents,” Picchione says.

She is not only a member of the disaster response subcommittee at GISCorps, but also one of the project managers for PhotoMappers. As the project’s subject matter expert, she provides advice on how to make the images that collect most useful to emergency managers. Her bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and master’s in technology and policy, as well as a previous job experience in the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) makes her a perfect fit at PhotoMappers.

“I’ve been with GISCorps since 2021, but before that, I was at FEMA where I worked closely with the team through numerous disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic,” she says. “When I left FEMA for a research opportunity at MIT, I joined GISCorps’ Core Committee so I could continue supporting a mission that’s very important to me.”

According to Torpey, the PhotoMappers project started out around 2017 as the brainchild of Paul Doherty, then with the National Alliance for Public Safety GIS (NAPSG) Foundation.

“The original version was a Survey123 form and an Attachment Viewer application hosted on ArcGIS Online,” she says. Now the project is more sophisticated and has “morphed into a dashboard, which was eventually replaced by a pair of Experience Builder apps developed by GISCorps Core Committee member Erin Arkison and a Hub site maintained by NAPSG.”

During the last seven years that she has volunteered with GISCorps, Torpey has held many roles, including working as a part-time program coordinator. Today she is a member of the organization’s advisory board. She still remembers her first official GISCorps projects where she participated in various coordinated mapping events, or mapathons, to support the polio eradication campaigns in Africa of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“Global health organizations trying to eradicate polio need to ensure that their vaccination campaigns reach every settlement,” says Torpey. “Because these settlements can be temporary and poorly mapped, they asked GISCorps to scour recent satellite imagery to find and digitize dwellings across vast regions. This data would then be used to estimate population sizes and plan vaccination efforts.”

Outside her volunteer role at GISCorps, Torpey’s day job is at a California-based environmental consulting company. After receiving her BA in geography from the University of New Orleans, she continued her studies and finished her MS degree in Geographic Information Science and Technology at the University of Southern California.

Torpey believes that people who are drawn to the GIS field tend to have a level of hyper-focus and attention to detail that comes in really handy for the kind of work that they do at GISCorps.

“We are happy to spend hours on end poring over every inch of a satellite image, looking for buildings and huts to digitize,” she says. “I imagine a lot of other people would lose their minds doing that after about 20 minutes.”

GISCorps activities at a glance. The organization coordinates short-term volunteer GIS services worldwide to communities in need.

And indeed, volunteers at GISCorps typically work on projects that require GIS skills, although not all the time. According to Elhami, the most sought-after services by organizations interested in requesting volunteers—referred to as partner agencies by GISCorps—are data capture and collection, as well as GIS application development. Other projects may also require data visualization, GIS training, data management, and remote sensing.

“The majority of the projects during our early days were conducted onsite,” says Elhami. “But that trend has reversed as almost all are done remote now.”

The founder of GISCorps has also observed that conducting GIS needs assessment has become one of the most requested skill sets.

“That’s mainly because in most cases the partner agency does not possess a vast knowledge of GIS,” says Elhami. “Volunteers must first learn about the PA’s line of business and determine how GIS can be helpful to them to be able to make sound recommendations and follow it up with subsequent actions.”

So can someone with no GIS skills become a GISCorps volunteer?

“Those without GIS expertise can still apply and join our PhotoMappers team,” she says. “That project does not necessarily require GIS know-how, though GIS experience is definitely helpful.”

Picchione agrees, adding how easy it is to get started with PhotoMappers since the team has already developed extensive guidelines, including a group of peers that can offer support.

“It’s also a great introduction to GIS,” she says.

“PhotoMappers would also not be possible without the help of GISCorp Core Committee members such as Erin Arkison and Monicque Lee,” adds Elhami. The organization also relies on 10 “star” volunteers who serve as recurring administrative members for the project.

For their work, the PhotoMappers team received in 2022 the Award for Excellence in Public Safety GIS from the NAPSG Foundation.

“As a partner agency, NAPSG Foundation fields requests for PhotoMappers activations from the emergency management community and shares the data widely,” says Elhami.

A good deed is its own reward

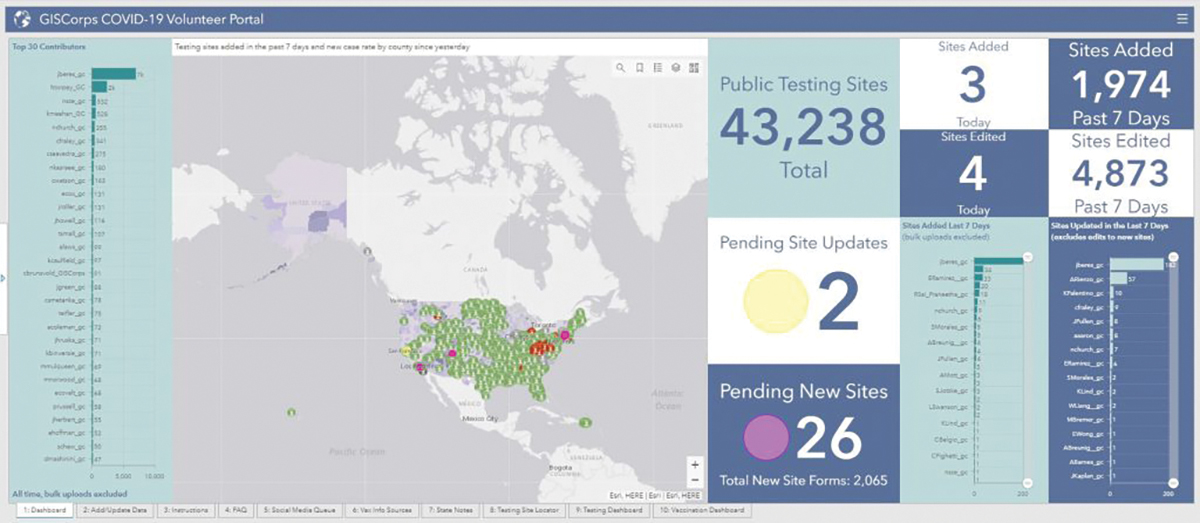

GISCorps helped in the mapping of testing and vaccination sites during the COVID-19 pandemic.Several studies have shown that participating in volunteer activities can help individuals acquire new skills as well as expand their network. One of them, a survey involving thousands of volunteers in Ireland, revealed that the amount of time dedicated to volunteering influences not only the number of skills developed by people but also their depth of skill acquisition. While another study showed that volunteering is mutually beneficial because it broadens the professional networks of both the participating volunteers and their recipient organizations.

“I think that what excites the volunteers about GISCorps can be summarized in three areas: Paying forward or doing good, networking with colleagues, and learning new skills,” says Elhami.

Yet aside from gaining new skills, volunteering has also been shown to improve a person’s health and wellbeing by enhancing their connection to others as well as their sense of community.

Torpey, for instance, feels grateful to have been part of a mapping project which has helped many people during the last pandemic.

“Jeff Baranyi, the disaster response program operations manager at Esri, contacted GISCorps at the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in hopes that we could gather some volunteers to help assemble a nationwide inventory of COVID testing site locations by integrating data shared publicly by state, county, and local health departments,” she says.

Torpey took the lead on that project, partnering with another nonprofit called Coders Against Covid. After 18 months of working with hundreds of volunteers, they were able to map around 70,000 testing and vaccination sites.

“That web mapping feature service has gotten over 20 million views,” she says. “Being part of that project was a surreal experience and an honor.”

The best parts of volunteering with GISCorps, Torpey says, include not only skills development but the opportunity to build one’s network and resumé. There is also the camaraderie of working with a team of like-minded people, while at the same time helping others in their time of need rather than just sitting on the sidelines wishing you could do something.

“Volunteering at GISCorps exposes one to people, organizations, and GIS-use cases that you might never otherwise encounter,” she says.

For URISA’s executive director, Wendy Nelson, GISCorps is a remarkable example of how GIS professionals leverage their skills to contribute to global humanitarian efforts. According to her, their work showcases the powerful impact that GIS technology can have on improving and saving lives.

“The dedication of these volunteers truly embodies the spirit of using technology for the greater good,” says Nelson.

Aside from people and technology, however, GISCorps also needs reliable funding to be able to carry on doing their selfless endeavors.

“While we have had amazing support from our volunteers and industry leaders, continued and sustained donations will ensure that we can continue and expand our work,” says Elhami.

Clearly the organization does not lack skilled people who are willing to map for free, but “it is important to mention that they may not be called to work on a project right away as we have more volunteers than projects,” she says. “We would love to get more projects either from the PAs or from our volunteers.”

To help increase their volunteer assignments, GISCorps partnered with Esri in 2017 and launched a program called the GIS Service Pledge (GSP). Through the GSP, the geospatial company donates a one-year ArcGIS personal use license to each volunteer who commits to contributing their GIS expertise to a worthwhile cause consistent with GISCorps’ mission and policies.

“To date, we have had 62 GSP projects and would love to see the program expand further,” says Elhami. “The GSP is an opportunity for volunteers to identify, design, and manage their own project supporting an organization, community, or cause that matters to them.”

GISCorps volunteers come from all over the world.

GISCorps, however, has a vendor-neutral policy in the recommendation of software, hardware, and other related technologies and services. “We work with or recommend what’s in the best interest of the organization,” says Elhami.

That is why their projects can also involve the use of open-source mapping platforms like QGIS or the OpenStreetMap, but the majority use Esri software even though they are a software agnostic body.

“When nonprofit organizations need help working with their software, Esri often refers them to GISCorps,” says Torpey. “We then have a brief scoping meeting with the organization to identify their needs, and then we recruit one or more volunteers with the skills required to meet those needs.”

Ultimately, beyond the technology, putting together the right people in any mapping task is just as important.

“Projects are successful when we put people at the center—when we listen with an open mind, treat each other with kindness and respect, and come up with creative solutions,” says Picchione.

That is why Elhami is impressed by the impact that the people behind GISCorps have had in the past 21 years.

“I’m proud of our volunteers as they instill my confidence in humans’ ability to do good without hesitation and monetary compensation,” she says. “I’m incredibly humbled by their generosity and willingness to give. I feel very lucky to get to know and work with them.”

GISCorps activities are possible thanks to volunteer work, in-kind donations, and services, grants, corporate sponsorships, and individual donations. If you would like to support GISCorps, visit their website at: www.giscorps.org/contribute/.