As the skipper of Galileo 3, a 30-foot sailboat on the Columbia River, I tell my crew that I am comfortable with 15 feet of water under the keel, get nervous when it drops below 10 feet, and take immediate action if it drops below 6 feet. That’s because I cannot constantly monitor my chart to avoid running aground. So, I was amazed to find out that the huge cargo ships that navigate the river for 100 miles from its mouth at Astoria to the Port of Portland sometimes have as little as two feet of vertical clearance.

This feat of navigation is made possible by the knowledge, skills, experience, and electronic equipment possessed by three sets of marine professionals who cooperate tightly: the river pilots who steer the ships, the hydrographers who survey the river, and the dredge operators who maintain the required depth of the navigation channel.

Maintaining a consistent minimum depth is essential to safe navigation. However, due to the very dynamic nature of the river’s bottom, keeping it navigable requires an endless cycle of surveying and dredging—a Sisyphean task costing more than $50 million a year.

The Hanjin London cargo ship, capable of carrying about 67,000 metric tons, transits the Columbia River channel on its way to the Port of Portland, the fourth-largest port on the West Coast.

The Port of Portland was created in 1891 by the Oregon Legislature to dredge and maintain the Columbia River channel at a depth of 25 feet. It now operates the fourth largest port on the West Coast as well as PDX international airport. The channel is now maintained at 43 feet of depth and a width of 600 feet, from Portland Harbor to the mouth of the river. The depth was increased from 40 feet in 2010, due to pressure from commercial interests, because each additional inch of draft allows a cargo ship to carry additional cargo worth up to several million dollars.

Division of Labor

The Columbia River pilots are usually the first to notice shoaling along the navigation channel, and they promptly report it to the Portland District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. USACE surveys the navigation channel and, through its project managers, passes the information to its two dredges and to one operated by the Port of Portland under contract. After dredging is accomplished, the survey boats go back in to check the channel depth.

Every day, USACE posts fresh survey data on its website that the river pilots use routinely and is freely available to the public. It also coordinates very closely with the U.S. Coast Guard, which is responsible for issuing notices to mariners.

The River Pilots

“When we transit the Columbia River, we look at current charts and at tide gauges to plan for two feet of water under the keel,” says captain Paul Amos, president of Columbia River Pilots. “That’s our requirement for a static vessel, though when a vessel is moving it can ‘squat,’ and that vertical clearance can be reduced by a corresponding amount. Depending on the time of year and the dredging work that the USACE has been able to do, it is common for vessels to have only a few feet of water under their keel on the Columbia.”

The pilots work very closely with the USACE, Amos confirms. “We meet with them at least once a month throughout the year and go over the most recent surveys for the entire river. The information on the surveys is combined with reports I receive from pilots on the route. We examine all shoaling and discuss the best way to proceed by prioritizing the problem areas to create a dredging plan based on best available information.

“Sometimes, pilots will notice variations in the way a ship handles while transiting the river, which may indicate a developing shoal before it has been picked up on a survey. We report that to the Corps who will survey the area as soon as possible and report their findings back to us. We then modify the dredging plan, if necessary, and pilots will adjust their passage plans accordingly.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

USACE is authorized by Congress to maintain the nation’s federal navigation channels for commerce, national security, and recreation. Its first mission, eliminating impediments to navigation on the Pacific Northwest’s rivers, dates back to 1871. The Portland District now manages 485 navigable river miles in the Columbia River Basin and also routinely supports the dredging needs of other districts along the West Coast and in Alaska and Hawaii.

For this navigation mission, the district maintains four survey vessels and two hopper dredges, which are seagoing vessels designed to dredge and to transport dredged material to open water.

The Survey Vessel Redlinger

The Redlinger, one of four survey vessels owned and operated by the Portland District of the U.S. Corps of Engineers, surveys the Columbia and lower Willamette rivers.

The Portland District’s survey vessel Redlinger, a 59-foot hydrofoil-assisted catamaran with a waterjet propulsion that makes it exceptionally maneuverable, provides a stable platform to monitor channel and harbor conditions and provide high-quality surveys of areas in need of dredging. It operates in any kind of weather over about 115 miles of the Columbia and Willamette rivers.

The vessel is crewed by Alan Stewart, a cartographic surveyor who was trained on the job by the Corps, and boat operators Bill Stillwell and James Kinney, both professional mariners with decades of experience. It conducts conditional surveys that, together with those conducted by two other USACE survey vessels, cover the river from Portland to Astoria every 30 days. “We have to,” says Michelle Helms, public affairs specialist for the district. “The commercial shipping industry works 365 days a year. We must have that data available for them.”

The Redlinger’s equipment includes:

- a single-beam Odom SMBB200-3 echo sounder

- a multi-beam Kongsberg EM 3002 echo sounder

- an Applanix POS MV, which receives differential GPS corrections from U.S. Coast Guard beacons and provides attitude, heading, heave, position, and velocity data

- an AML oceanographic sound velocity probe, and

- a computer system with HYPACK hydrographic survey software.

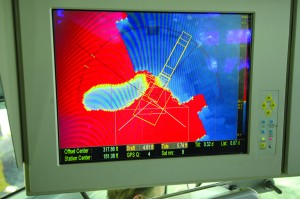

Stewart looks for shoaling using both of the echo sounders, which are attached to the bottom of a tower that extends 4.5 feet below the boat’s waterline when deployed. They are accurate to within half a foot and provide soundings 10 times per second.

“When we run a multi-beam, we are basically painting the bottom,” he says. “With the single beam, we will usually run channel lines, up and down the river. It just depends on what they need to see in the office for their volume computations.” When he is pointing the beam at a 45-degree angle, its swath is about two times the depth.

The information displayed on Stewart’s monitors includes a profile from the single-beam trace, data on the intensity and quality of the beams, the cross track, the depth in meters, heave, pitch, and roll, and a coverage map. He focuses especially on the tides, the boat’s position, which is measured with sub-meter accuracy, and its “squat,” which is its position in the water depending on its speed. “You can monitor it based on speed or RPMs,” he explains. “In general, RPMs is the best way to monitor it.”

To perform a Class A survey, he points out, they slow to less than 10 knots. For conditional surveys, however, the requirements are looser and they can go faster. In a typical day, the Redlinger will cover seven lines, each about three to five miles long. Stewart also keeps track of the speed of sound in the water, using data from the sound velocity probe, and adjusts his soundings accordingly.

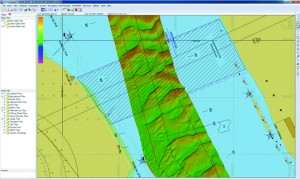

“With a conditional, single-beam survey, we are not looking for full coverage,” says Stewart. “In fact, on the chart they will plot the data with 70-foot spacing between each data point. These conditional surveys are a spot check. Then, when something doesn’t look right, we’ll come back in and really cover it with a multi-beam and get a really good coverage, without leaving any gaps.”

Stewart edits an XYZ file adjusted for tides, heave, pitch, and roll and sends it to the office, where they use it to calculate the volumes of sand that need to be dredged. It then plots these volumes on a chart and sends it to the dredge.

On the day I spent a few hours on board, the Redlinger was conducting a regular, seven-line, single beam conditional survey, up and down the river, checking for shoaling. Whenever it approached a tide board, the crew slowed down and approached it to read it, so that Stewart could subtract the tide from his soundings.

One of the two hydrographers at the office (or Stewart) produces a survey line, using HYPACK. The operator then keeps the boat as close as possible to that line—while also watching for underwater obstacles and surface traffic (ships, kayaks, etc.), monitoring radio communications and engine gauges, and periodically alerting Stewart to changes in engine RPMs. This is an exhausting job requiring a lot of concentration, as I experienced during 20 minutes at the helm.

The boat operators know many of their colleagues on other vessels and have a cooperative relationship with them. “These guys know us, they know our game, what we do every day,” says Kinney. “A lot of them will get out of the way for us, because they need this survey. They need to be able to go online and find out what’s going on at all times.”

Portable Pilot Units

Like most pilot groups, Columbia River pilots carry Portable Pilot Units (PPUs), laptops loaded with custom-made software for the Columbia River System, which serve as a Vessel Traffic Information System utilizing the Automated Identification System signal from other vessels. The PPU program for the Columbia River pilots was developed for them by the Volpe National Transportation Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Captain Paul Amos, president of Columbia River Pilots, says, “Working with USACE and Volpe, we pioneered the ability to download the most recent USACE surveys to our PPUs, which we carry onboard with us. Within a few days of completing a survey, the Corps will post it on its website. The software on our PPUs will download the surveys and install them on our laptops so that we always have the most recent information available to us on the ship. We can also access NOAA sensors located throughout the system that give us real-time information on river levels. These features help us to monitor our expected under-keel clearance during a transit.”

The Dredge Oregon

The Port of Portland owns and operates the dredge Oregon, which maintains the Columbia River navigation channel on behalf of USACE and other ports in the region. The dredge operates around the clock, six days a week, typically from June through January each year, working from the Columbia River bar to Portland Harbor.

The dredge is propelled by two huge spuds at its stern, so it moves forward slowly while swinging from side to side. “We are doing a series of arcs down the river,” says captain Mark Stillwell, who commands the dredge’s 45-member crew and has a 35-year nautical career. While the channel is officially 600-feet wide, the dredge clears an “over-width” of 50 feet to 100 feet. “This allows six months of time while we are off the river,” he says.

How much it can dredge each day depends largely on the slope of the river bank. This season the distance traveled varies from 250 to 800 feet in a 24-hour period, moving an average of about 25,000 cubic yards in that same time interval.

To relocate the material it removes from the bottom, the dredge uses pipes in sections 60 feet to 100 feet long, which are constantly repositioned as the dredge moves, and a pump powered by a 5,000 HP engine. The dredge’s cutter head, powered by an 800 HP engine, is attached to the end of an 80-foot “ladder” that protrudes from the bow of the vessel and is suspended by cables. The leverman, who operates the cutter head from the top of the dredge’s tower, continuously adjusts his swing and depth on the basis of such variables as the tide and the vessel’s pitch. Because the dredge’s survey-grade depth sounder is on its bow, it is always behind the cutter head, though by less than the length of the ladder, which is deployed at an angle.

Using all the Data

“The Corps gives us target depths and tolerances,” says Doyle Anderson, navigation manager for the Port of Portland’s navigation division. “We meet with the river pilots once a month and review digital maps. They help us prioritize. There are areas on the river that tend to shoal up the same every year. But there are other areas that only shoal up over time, and so it may be a couple of years or three or four years before we come back there. We can do advanced maintenance dredging up to as deep as 48 feet.”

“We survey our placement sites so that we can understand how much material we have placed there and that we have placed it within the permitted site,” Anderson explains. “After placement of the dredge material, we survey it again so that we can calculate the quantity of material that we have placed and then to understand the remaining capacity of that site for the future dredge material placement.”

To tie the bathymetric surveys to land surveys of the islands created by the dredge, the Port’s surveyors use the Columbia River datum. “It is a sloping datum for the Columbia River, and all of the sites are tied to that,” says Anderson.

To transfer elevations they use GPS. “Then, they will take an actual level shot on the water and read the tide gauge to compare it to the Columbia River datum as well. It is not highly precise topographic mapping. We are relying on GPS to do these surveys and we are mapping them as if we were going to draw, maybe, two-foot contours.”

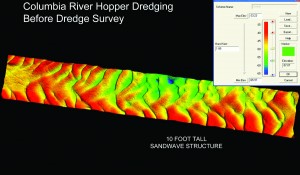

The Port’s hydrographic surveys are denser than those performed by USACE. “Their lines are 150 feet apart, so they are a snapshot of what they have in the river,” says Travis Brennan, the Port’s hydrographic surveyor. “The river pilots give us a synopsis of what they have and what they need us to do, then we come out and do 50-foot spacing. We will also give data to the dredge every 25 feet down from those 50-foot lines. USACE defines the area from running up and down the river and we define it tighter. The Redlinger’s are the official surveys. Mine are progress or quality control surveys.”

“I come in initially ahead of the dredge, and I get a pre-dredge condition as it is,” Brennan explains. “That is what is loaded onto the screens on the dredge, and they work on that. Every day or every other day, I will do a condition survey that tells me how they are doing on their digging. I send them to the Corps and give them to the captain and the leverman, and they look at them to see how they are doing, whether they are holding grade, whether they are right at 47 feet, and so on. They are usually within a foot, which is amazing to me.”

“Our survey really helps the levermen understand how to control the dredge, how fast they should be swinging, and how much material is in front of them,” Anderson points out.

Brennan also adds a contour line to show the dredge operators what their goal is. “Even though they have all the numbers,” he says, “I give them a line that will define areas that need to be dredged and areas that do not need to be dredged. Recently, the levermen have wanted decimal places on their soundings, which is just a selection on my part. So, when they see a 47, they want to know whether it is 47.2 or 47.8 or 46.8. So, I give them that in the progress surveys, also.”

To conduct his hydrographic surveys, Brennan uses a 27-foot boat with a single-screw inboard engine. “It has a single beam echo sounder and a WAAS GPS receiver with 3-foot to 5-foot accuracy, but we are probably within 1/10 of a foot vertically, which is more important than our exact position,” he says.