Professional cartographer Evan Applegate shares his mapmaking process, including what’s inside his toolbox. He also tells us why in-person feedback is important to become a better mapmaker.

For something that was invented some 5,000 years ago, it is surprising to know that maps remain relevant in our virtual age. Our need to know where we are and how to make sense of our surroundings is very much embedded in our psyche that we have not grown tired of marking our locations on clay, paper, and now on digital screens.

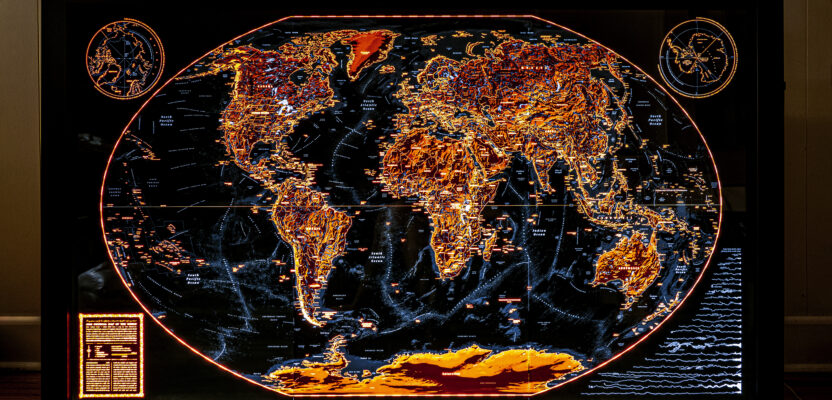

Applegate was commissioned by friends to create this three-foot-by-five-foot backlit world map to mark the important places in their lives. The map uses the Winkel tripel projection and shows water bodies, U.S. national parks, countries, capitals, and mountain ranges.

“No one hates maps, they have unparalleled vibes,” says Evan Applegate, a prolific cartographer who made it to xyHt’s list of leading geospatial professionals to watch this year. “Notice how phone maps use the same visual conventions of a paper map, which haven’t changed for a century: north is up, green is forests, blue is water, etc. The foundations of traditional cartography live on, mostly unchanged, in the digital age.”

He’s right. Google Maps, for example, uses traditional cartographic depictions to help over a billion of its map readers to find their way. Another popular digital map that has a tried and tested user-friendly layout is Great Britain’s OS Maps app. According to Ordnance Survey, the app’s developer and the country’s mapping agency, OS Maps has an average of one million users per month, and its revenues have already surpassed the sales of its own paper maps.

Yet custom-designed cartography is also booming. As reported in an article in the Wall Street Journal last year, bespoke and printed maps are the latest must-have among millennials and the Gen-Z crowd who swear that the quality of beautifully drawn charts helps not only in wayfinding but also “enhances one’s journey.” These handmade maps are now hanging on walls as art works, reminding people of their previous travel destinations or inspiring them for their future journeys.

Evan Applegate in his workshop working on a six-foot-by-four-foot illuminated map of the Hudson River.

“There will always be room for high-effort handmade maps,” says Applegate who specializes in ultra-detailed backlit maps. “If you want a map that will grab the attention of a viewer and be worth inspecting years down the line, you need to hire a cartographer.”

With 13 years of professional mapmaking experience, Applegate knows what he is talking about. Aside from drawing maps, he also actively engages with fellow cartophiles and mapmakers via his websites and podcast platforms. He admires the work of Daniel Huffman, Léonie Schlosser, Rodica Prato, Jamshid Kooros, and Alex McPhee, just to name a few of today’s mapmakers whose skillful and exciting designs are spurring a resurgence of interest in the cartographic arts among the new generation.

“You no longer need a mapmaker to turn data into a visualization. A half-dozen web tools can do that now,” he says. “But as the market floods with machine-generated maps, you can differentiate yourself by the human touch.”

Were you always personally interested in drawing maps when you were a kid?

It’s funny, but I never drew maps as a kid. Art was my least favorite subject in school because my hands could never render what was in my mind. Adobe Illustrator was a revelation because unlike my clumsy fingers, the computer could draw straight lines.

What was your dream job as a kid?

I wanted to be an astronomer. When I was 9, I visited a Jet Propulsion Laboratory clean room where the Deep Space 1 probe was being assembled. I still have the picture of me in a white smock and hairnet with the biggest smile I’ve had before or since.

Trees of the Tongass National Forest: Applegate’s favorite backlit map, which he created with lettering by Ezra Butt and illustrations by Matt Strieby and Aiyana Udesen

What is the very first map that you remember drawing?

I was 23 and working as a graphics editor for Bloomberg Businessweek. Graphics editors are like reporters who make charts. An editor requested a small locator map to accompany a story. I’d never made a map, but you don’t tell your boss ‘I don’t do windows’ so I grabbed an SVG map from Wikipedia and added a dot and a label. So, my first map was about half the size of a playing card and looked terrible. I was hooked.

Do you have any mentors or cartographers who you look up to?

Two people were huge influences on me: Tanya Andersen, an excellent cartographer who ran the University of Wisconsin-Madison cartography lab and helped me apply for a critical internship at National Geographic Magazine. Then there’s my mentor Daniel Huffman, a freelance cartographer who would work on his projects in Tanya’s lab, and at whose elbow I learned the craft of mapmaking.

Daniel is among the best living cartographers and a sterling educator. He is top-10 talented, generous with his time, and relentlessly encouraging to beginners. I hope to propagate that spirit.

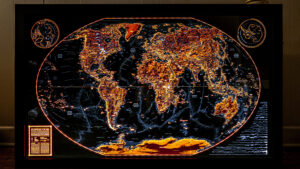

A four-foot-by-three-foot backlit shaded relief of California.

So how can we encourage the next set of cartographers to put their work out there?

I think it’s less that they need to put their work out into the wider world and more to get it in front of a few good mapmakers who will give in-person feedback. Emphasis on in-person. You can’t replace the experience of sitting with a good cartographer while he or she marks your map with a pencil. It’s not easy to get in that room, but it’s still possible. Get an editorial-mapping job, attend a university with a cartography lab, or travel to meet your favorite mapper.

In general, how does your mapmaking process begin?

I start by gathering too much data in an oversized extent-box. You never regret having an extra tangle of lines just outside your projected size because it’s much easier to crop down than expand out. Then I delete what I don’t need in QGIS/GDAL/OGR. Modern cartography is about thinning out a hairball and making the remainder look good in Illustrator and Photoshop.

Where do you draw your inspiration to create a map?

I look at maps from the 1910s to the 1980s for guidance on color, hierarchy, and composition. Mapmaking is about applying old solutions, again and again, polishing what works. I haven’t seen a cartographic innovation created in my lifetime that will outlive its author.

And what’s in your toolbox?

To make my maps I use QGIS, GDAL/OGR, Avenza MAPublisher, Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign, and Eduard. For making custom tiled basemaps, I like Mapbox Studio.

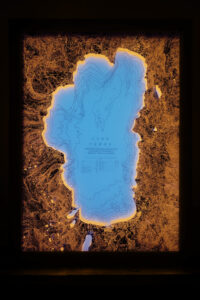

A nine-inch-by-12-inch bathymetric map of Lake Tahoe and its environs.

How about coding or programming to create maps?

Oh yeah, thanks to large language models I finally have an English-to-code translator. What used to take hours on Stack Overflow now takes seconds. I can boil down huge TSVs with Python, automate what used to be a QGIS pointy-clicky task, create web maps with JavaScript, even prototype Flask web apps.

Here’s a message to other cartographers: machine learning offers leverage. Computers can do mediocre work better than you, so use the computer to attack more ambitious projects. You’ve been handed new power tools, they’re very cheap, and you should learn to use them to make maps you couldn’t attempt before.

Do you have a favorite map that you made yourself?

My favorite map is “Trees of the Tongass National Forest,” which I made in 2018. I was then a GIS temp for the U.S. Forest Service in Arcadia, CA. I wanted to create something with a low-tech feel, so I hired other artists to add illustrations to map the world’s largest intact temperate rainforest. The best part is it is public land, so you can head there today and camp for a year in a stunning roadless wilderness.

Please tell us about how your website The Map Consultancy started?

I had graduated UW-Madison and moved to Los Angeles in 2017, and I wasn’t going to return to Bloomberg Businessweek. So, I started freelancing under a new brand and subcontracting any work I couldn’t handle myself.

What was the most difficult challenge that you faced during those first days of starting out?

Marketing was my big challenge. Many independent cartographers have a niche, but my portfolio is scattered. I have maps for National Geographic, a map for a self-published treatise on the lost city of Atlantis, an asset map for a giant oil company, an illustrated map of the plants of Los Angeles, etc. So instead of selling myself as “I make X maps,” I pitched myself as a fast, independent problem solver: send me your data and, with very few emails, receive an effective and attractive map.

And now you also have another website, Radiant Maps. Tell us how it complements The Map Consultancy.

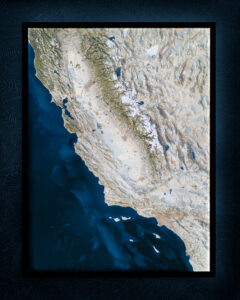

I’m glad you asked because those maps are my favorite. In 2019, I envisioned a map with all the fine detail of a paper lithograph, but with an attractive no-eye strain glow. I figured out how to print maps on 3,600 DPI film negatives, which look like high-resolution monochrome overhead transparencies with only two tints: black and transparent, then halftones in between.

I backlit these films with warm-toned LEDs and they look great because you get super-fine lines down to 150 microns. It’s a whole little universe of detail. They make excellent office art, and you can view them at radiantmaps.com.

And how about your podcast Very Expensive Maps. Is it easy to get mapmakers to talk about themselves and their work?

The mapmakers I interview are happy to talk. I started the podcast because I wanted to satisfy my curiosity on how great maps get made. Podcasting tools are essentially free, so I thought I’d let the internet hear what they had to say.

My one interview tip: don’t interrupt. I write four or five questions ahead of time, keep a few of their maps open on my screen and let them speak freely on technique, influences, hassles, all of the work that goes into a high-effort map.

And lastly, is there any message that you would like to share with our readers?

The best maps are not behind us. They will be made today by people who cared enough to make them. Tom Patterson, formerly of the National Park Service and responsible for dozens of great recreation maps, told me, “Now is the golden age of cartography.” It has never been easier to make a high-effort map. Computers are cheap, many tools are free, and the web is flooded with inspiration and tutorials. You just have to start turning the crank.