By Matteo Luccio

The 3D data collected with laser scanners and digital cameras can be used to create digital and physical 3D models that have myriad applications—from marketing a new building to routing first responders in an emergency. Among the companies that produce these 3D models are Zoyes Creative, based in Detroit, Michigan, and founded by an architect, and Zelus, based in Phoenix, Arizona, and founded by a contractor.

ZOYES CREATIVE

An Architect’s Perspective

Phil Martin, senior illustrator and model maker at Zoyes Creative, earned a master’s in architecture at the University of Detroit Mercy, like the company’s founder, Dean Zoyes, did years earlier. Most of the company’s clients are real estate developers who found out about it through word of mouth, Martin says. “Dean has been making models since he was in college. He bought his first laser cutter back in 1999.”

Source Data

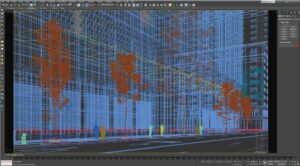

3D modeling begins with the geometry being captured and modeled using Google Earth as a 3D Reference (Figure 1) for measurements and location data, as well as photo references.

The data that Zoyes receives for use in making both physical and digital models depend mostly on the client’s technical sophistication—ranging from simple 2D CAD drawings and elevations, which require a little more work upfront, to, occasionally, BIM models or GIS. It comes mostly from Autodesk programs, such as Revit, AutoCAD, or 3D studio.

Some clients provide “huge swaths of information that we have to pare down,” Martin says. “If we need it, we have the entire building at our disposal. If we do not need to see where every paper towel holder goes, I can use the Revit model or the BIM and select what I need, type by type.”

Then the wireframe model has materials applied and lighting set up, based on the real-world location (Figure 2).

Sometimes clients provide material samples that Zoyes photographs or scans to create physically based rendering tiles, with the proper texture and roughness. “I will see the color of the material or switch layer to see its reflectivity,” Martin says. “All these different layers build up and get painted onto my model.”

Zoyes rarely scans buildings, because most of its clients are far away and large enough to collect the data themselves. It also does not deal with lidar point clouds. “The information from a point cloud is not very useful to me,” Martin explains. “Once it has been converted to an actual geometry or line work, such as topography lines, we get our hands on it. By that time, the architect has already scanned the site, created a site plan, and designed the building, and he will give us the BIM data.”

Deliverables

For a digital deliverable, typically Zoyes produces a 2D image that can be used for print collateral or a billboard, but sometimes it produces completely rendered video content. While the output is different, the production method is the same. “Everything is built into our 3D model,” Martin says. “I will take all the 2D drawings and tilt them up into elevations in a 3D space. I can also take all the topo lines, drop them down in the Z axis until they are in the proper location, then drape a digital fabric over them to create the topography I need.”

After creating a model, Martin can add textures and lighting. He creates and textures the model using 3D Studio Max, an Autodesk program that has a powerful modeling and rendering program, and V-Ray, which is

a rendering engine. Within 3D Studio Max he sets up virtual cameras, specifying the settings as if he were a photographer — such as the film speed, the F-stop, and the shutter speed. “After everything is set up and we like the way it looks, we run some tests,” he says. “If it looks good, we will shoot the final image. If we are producing a video, we will make sure that the camera is following all the pathways through the project and render them frame by frame.” For the final production of VR “walkthroughs,” he switches to the video game rendering engine Unreal Engine.

“The things we produce are almost like artworks that are developed near the end of the process for very polished pieces of imagery that are used to help sell projects,” Martin says. “Occasionally, they are used to help inform design decisions or come up with some ideas about how they might want to change the space, but, for the most part, we come in very late in the project.”

To produce physical 3D models, Zoyes uploads topographic data to a milling machine that sculpts high-density foam to look like the topography of the site, then paints them. “They could be used in a sales center to show people a new residential development.

ZELUS

A Contractor’s Perspective

Ken Smerz, Zelus’ CEO, started the company about 10 years ago. “I was a contractor, so I understand the value of having accurate dimensional details and a digitally-driven construction process,” he says.

His clients are mostly architects and owners, but also contractors and engineers, and his markets include distribution centers, semiconductor fabrication, bio-pharma production, data centers, hospitals, airports, offices, entertainment, multi-site retail, and industrial sites.

“They are contacting us to accurately understand their existing conditions and we help them create a digital twin.” Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he points out, many people are repurposing their spaces, which is good for his business.

Zelus currently employs more than 125 people to scan, register, and create deliverables throughout North America and, pre-pandemic, other continents. It has an in-house R&D team that continuously tests hardware and software.

In North America, Smerz says, the market for 3D models is heavily driven by vertical structures. His clients use his models mostly for virtual design and construction (VDC) and building information modeling (BIM). This includes pre-fabrication, clash detection, reduction in rework, reducing RFIs, QA/QC, and spatial design/planning. Owners can also use them for security planning, maintenance recording, and COVID-19 repurposing.

Scanning Projects

Among his company’s recent projects, Smerz cites the scanning of 1.8 million square feet of space in the New Orleans Superdome for a major renovation, which included modeling 325,000 interior objects, and of a little more than 1,000,000 square feet for Google of buildings in Chelsea Market, an iconic landmark in Manhattan.

“We scanned out there for a long time, then we created a BIM that was used by the architects, by the contractors, as well as for security planning and wayfinding for EMS or police,” he recalls.

Zelus has a full-time field scanning team. “We typically scan 6,000 positions per week using lidar, but sometimes more,” Smerz says. The company uses terrestrial, mobile, and airborne laser scanners from Leica, Trimble, Faro, Matterport, and other vendors—as well as photogrammetry and video.

Zelus’ staff includes 18 FAA-certified UAV pilots who fly mostly for big box retailers and create highly customized models. “They love the UAV footage, lidar from UAVs, photogrammetric data capture, and HD video. Our data enables them to see their rooftops and A/C units,” Smerz says. Sometimes these clients also want flatness reports that they can use to predict where pooling of rain or snow will occur.

Deliverables

Zelus’ deliverables depend on the end user. “An architect will use it differently than intel,” Smerz explains. “Semiconductor users will use the data differently than Target stores or Regal Cinemas.”

Deliverables include registered point clouds, 2D as-builts, 3D models in any software, contour/topo maps, floor flatness reports, and HD still and video tours. The company can also provide file formats that support a variety of 3D printers but does not do any 3D printing in-house.

When a client wants the ability to conduct remote inspections, Zelus uses the HD imagery it has collected to create a virtual tour of a location or facility that the client can access via a portal. The client can then also download the data for other uses.

“All our work can be incorporated into GIS and is utilized in CAD/Revit design,” Smerz says. “We also create a variety of BIMs in different file types—as the customer requires.” However, he points out, the use of 3D models in GIS is still in its infancy. “Probably 95% of what Zelus produces is not taken back into a GIS data set.”

Wish List

What would help Zelus the most, Smerz says, would be a software program that did full feature recognition. “If we could scan an environment—such as a hospital, a hotel, or an airport—and have feature extraction and feature recognition from the point cloud itself, that would be fantastic.”

As for hardware standpoint, he wishes that mobile units used indoors had the accuracy required to scan large structures, such as airports. “People are working on that. We do a lot of testing with our in-house R&D group. But there is room for improvement there.”

The final step is to render an image using Vray, to create a realistic and polished image for the end user.