What impact will allowing flights beyond the visual range of the operator have on the mapping industry?

Ever since the introduction of uncrewed aviation platforms (drones) for cartographic purposes over a decade ago, we have seen a proliferation of use cases in which photogrammetry and land surveying companies alike have adopted the new technology, but, for regulatory reasons, only for small areas and relatively easy projects.

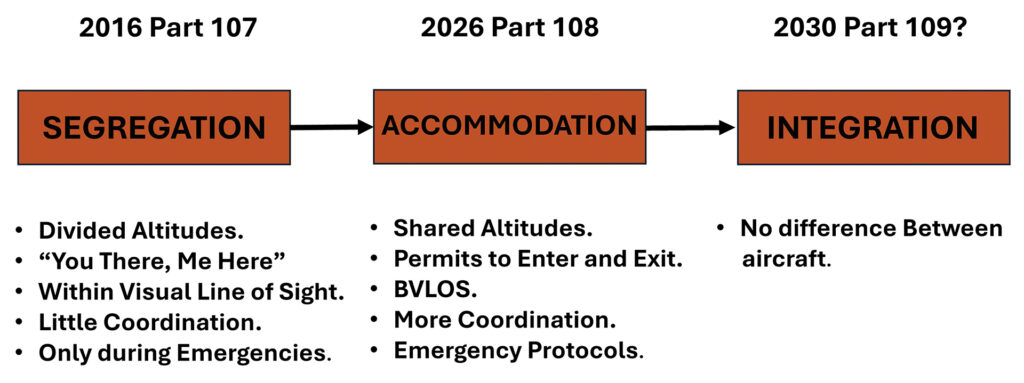

The reason is simple, in the summer of 2016 the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued its Part 107 regulation in which drones were finally allowed to use the National Airspace (NAS) under very strict conditions such as flight altitude and most importantly for our industry, flight distance to the operator.

This key restriction to maintain the aircraft within the visual range of the operator meant that uncrewed aircraft had to fly only a few hundred yards away from the pilot in command (PIC) to be a legal mission. This is a major obstacle to photogrammetric flights which normally cover hundreds if not thousands of square miles on each mission to minimize costs and take advantage of clear and cloudless days. When the operator is using a small multi-copter, this visual restriction seems to be less of a problem, because of the short battery life of most of these commercial platforms. With existing fixed wing platforms, especially those with hybrid powerplants, Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) limitation imposes a costly external restraint.

This key restriction to maintain the aircraft within the visual range of the operator meant that uncrewed aircraft had to fly only a few hundred yards away from the pilot in command (PIC) to be a legal mission. This is a major obstacle to photogrammetric flights which normally cover hundreds if not thousands of square miles on each mission to minimize costs and take advantage of clear and cloudless days. When the operator is using a small multi-copter, this visual restriction seems to be less of a problem, because of the short battery life of most of these commercial platforms. With existing fixed wing platforms, especially those with hybrid powerplants, Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) limitation imposes a costly external restraint.

Wingtra aircraft ready to take off in a photogrammetry mission in Chile.

During the recent Commercial UAV Expo in Las Vegas, the most important industrial drone event in the world, officers from the FAA announced their intention to publish a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) for Part 108 soon, but details about a specific date were sketchy at best.

What will Part 108 be and why is it relevant to our industry? Part 108 is an improvement over Part 107 in many ways, but especially in what the industry refers to as BVLOS or flights beyond the visual range of the operator. In other words, uncrewed aircraft will be able to fly away from the pilot in command as far away as they can as long as communications are maintained 100 percent of the time and with 100 percent reliability and redundancy. And this is perhaps why the FAA is taking its time enacting the regulation. Guaranteeing 100 percent reliability and redundancy is not an easy task, but ingenious solutions are being proposed to prove to the federal agency that drones are ready to safely join their counterparts in the National Airspace (NAS).

Long corridor project executed in one continuous flight under a BVLOS waiver.

While we wait for the FAA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) industry, and academia to solve the many technical questions involved in a full integration, let us focus on the mapping industry and how this upcoming legislation will affect it.

The current status of the Part 108 regulation is a bit foggy, but with the signature of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 signed by President Biden on May 16, 2024, the federal agency had four months to publish its much-anticipated NPRM. That date, September 16, 2024, came and went without a word from the federal agency except a commitment to publish the NPRM before the end of the year.

Using previous experiences with FAA’s NPRMs we can safely forecast that the earliest we will have a formal regulation that would allow BVLOS flights is in the first quarter of 2026. That means that in less than 18 months photogrammetry companies will be able to use fixed-wing drones at higher altitudes and for longer periods of time. As we all know too well, these two characteristics, altitude and time in photogrammetry only mean one thing: more area.

It would be useful to analyze which of the existing non-piloted aerial platforms would offer the best options and would benefit the most from the new regulation:

- AgEagle eBee aBee X: 90 minutes flight time; can map 1,235 acres at 400 feet altitude with a 3.6 pounds of useful load.

- Wingtra One Gen II: 59 minutes flight time; can map 1,140 acres at 400 feet altitude with a 1.8-pound useful load.

- Quantum Systems Trinity Pro: 90 minutes flight time; can map 1,729 acres at 400 feet altitude with a 2.68-pound useful load.

- Delair UX11: 80 minutes flight time; can map 300 acres at 400 feet altitude with a 1.5-pound useful load.

Now that we have established that we can cover more area with a fixed-wing drone, let us analyze a case study that will take full advantage of more altitude and no visual restrictions to the operator.

Public Utility Corridor

This project was executed under a special waiver or Certificate of Authorization (COA), which authorized the lines to be flown away from the visual range of the operator. It is important to note that after Part 108 is enacted, missions like this will be possible without special permissions. The parameters for the project were as follows:

- Length of corridor: 12.42 miles

- Width of Corridor: 1,500 feet

- 80 percent longitudinal overlap

- 70 percent lateral overlap

- GSD: 1.2 inches

The flight was executed using a Wingtra drone with a 42 MP camera and a 35 mm lens. The specifications for the flight to comply with the project requirements were:

- Altitude of Flight: 820 feet

- Speed of Flight: 31 knots (36 miles per hour)

- Four useful flight lines

- Total flight time: 6.1 hours

This is the typical project that would take days to accomplish with a regular multicopter in Part 107 world, because of the combination of altitude restrictions and flying time.

The author’s version of what uncrewed aviation full integration will look like.

Even though we realize that Part 108 is still at least 12 to 18 months away, it would be useful to start exploring non-piloted aerial platforms that can offer the best performance in a regulatory environment in which we can fly our aircraft for more than one hour and cover hundreds if not thousands of acres a day, depending on the accuracy of the project.

We are still years away from a world in which crewed and non-crewed aircraft will share the national airspace freely and without restrictions, but this time will come, and we will see a full integration of both platforms surely within the next decade.

At that point fixed-wing drones will be able to more closely compete with traditional piloted platforms, but as we prepare for that futuristic prospect it is good to think that aerial mapping and photogrammetry are becoming more and more accessible to land surveyors all over the world.