Using a drone processing service can make firms, large and small, more competitive. AI is working wonders for specific steps, but can’t do it all. Vendors and users are finding out how imprtant the human elements is.

Drone-based aerial mapping and surveying has evolved, over this first decade of adoption, to include a significant amount of automation, including AI applications. However, the skill, experience, and judgment of humans remain a crucial element.

Surveying, engineering, construction, and mapping firms of all sizes have adopted drones as a part of their standard kit. The hardware has become somewhat commoditized, and there is a lot of amazing software out there. One can easily plan and execute their drone flights, and there is a plethora of software to process and manage the data. In some ways, the flights are the easy part; mastered with a moderate amount of training. However, the processing phase can put a premium on training and experience. It is not a surprise that many firms are turning to drone processing services, tapping into a pool of experts at the ready.

An example is TD&H Engineering, a respected full-service engineering consulting firm. Headquartered in Great Falls, MT, they have offices in several states across the country. “We use aerial mapping, with our drone for about 60% of our projects,” said Darryl Witter, PLS, a survey project manager for their Spokane WA operation. “These range from small design lot surveys, larger design projects, ALTA surveys, as-builts, municipal, energy, utilities, and more. Aerotas [a drone services provider] has been there for TDH over 6 years with support questions and answers for any type of issue I have come up against to obtain the best deliverables. They’ve supported us from purchasing equipment to planning and then ultimately the final deliverable for each request regarding the clients requirements.”

Witter went on to explain that the combination of their in-house expertise in establishing project control, setting GCPs (ground control points), planning aerial campaigns to meet their precision and accuracy needs, and flying the sites, followed by processing through a service has been very powerful. This workflow has even changed how they approach projects. “If we are doing a project for a municipality, we often fly the whole city or town, have the orthophotos and planimetry created, and then we can use this on subsequent phases and new projects,” said Witter. He also noted that aerial data is a valuable tool, for instance, in helping make determinations of adverse possession (that would be a great subject for another article).

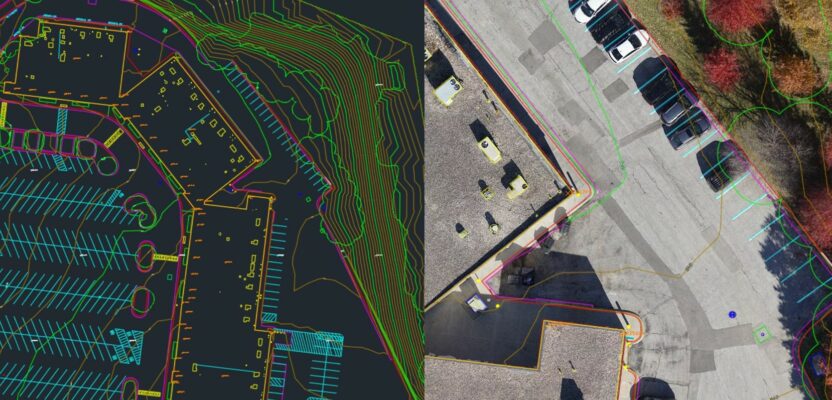

The customer sets ground control, plans and executes the fights, then the drone services vendor does the processing – Source: Aerotas

Growing With the Market

“We didn’t start with the goal of being a drone processing firm,” said Logan Campbell, CEO of Aerotas. “I started my professional education in statistics. I’ve always been an aviation enthusiast, and my hobby was building radio control planes; this led to building drones. The idea for Aerotas started with a graduate school project seeing if I could help businesses work with drones, looking at where I could apply my mathematical analysis background to the math and science of photogrammetry. We were a little early on in the arc of drone applications before the technology caught up with what we wanted to do.”

Campbell explained that the name Aerotas is a mix of “aero”, Greek for air, and “veritas”, Latin for “reality”. Just over a decade ago, drones were a new thing. The prospects of using the relatively primitive types of drones and software at the time and turning these into something that could produce accurate and reliable data seemed daunting to many. The original iteration of the company was focused on helping people use drones; training and providing support. “In those early days of drone use, there was little drafting from the data,” said Campbell. “The cameras and software weren’t as great, and lidar was prohibitively expensive; many users simply wanted aerial images as a visual aid, to examine features and conditions on a site.” Starting around 2014, as the adoption of drones accelerated and the tools improved, processing entered a new era. In particular, photogrammetry became the key. Campbell said that teaching photogrammetry to drone users was not easy, as there was an experience premium. A new focus for the company became processing the aerial data for the customers. And then things took off (no pun intended).

Services

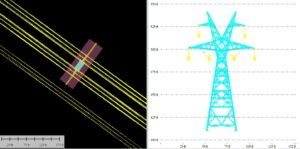

Customers provide Aerotas with the images, lidar if they have it, the GCPs, and GNSS/INS (inertial navigation system) data (if applicable). Aerotas will process the images and/or lidar, post-process the GNSS/INS (PPK), create orthophoto mosaics, and draft 2D or 3D planimetry, per standard or custom orders. “Over time, we continued to expand our portfolio of deliverables,” said Campbell. “We added more and more projects from custom drafting to specific linework that can be imported into CAD and design software. We work with a lot of formats. And we now accommodate certain ultra-specific types of projects, like powerline surveys.”

Aerotas has a pool of highly skilled staff distributed across the country; each with a broad base of experience. They utilize a wide range of software; most of the standard packages, but also some they have developed in-house. They can choose from multiple packages to suit the project specifics, but often it comes down to the preference of their staff and/or the customer.

While many of the packages have incorporated elements of AI, for instance in point cloud classification, Aerotas does not over-rely on it. “AI can be great, but it still misses too much,” said Campbell. “We, and our customers, have found that having the “human-in-the-loop” is the best approach. We cost-effectively produce top products, with the key decisions made by a skilled practitioner.” Campbell notes that the predominant type of data they process for customers is images. “There are many advantages to photogrammetry, as opposed to trying to use colorized lidar; there is so much more that can be seen, “ said Campbell. “For example, lidar may not provide sufficient definition to detect a maintenance hole lid on flat pavement; whereas it is quite obvious with images.” Lidar can have advantages, like features in shadows or under canopy. Combining images and lidar can also be very powerful, but as Witter noted, they can do what they need to do with images alone for most projects.

You can order services online; some at set prices (e.g. orthophotos), and for other requests, they provide a cost estimate. “We are very big on the set price from a rigorous cost-estimate,” said Campbell. “We have a very complex matrix for developing estimates, that includes the computer time and human hands-on time. We set a fixed price that our customers can rely on; no surprises.”

While they do have some international clients, Aerotas is focused on the U.S. market for their services. Campbell explains that the standards and regulations of a single country are much easier to master and accommodate, plus he says that there is plenty of room for growth within the U.S. There are few engineering and surveying firms that do not already have or are planning on adding a drone.

Trust and Responsibility

A hot topic within professions like land surveying is “responsible charge”, a term often used when describing elements of activities that fall under a licensee’s direct supervision, and ultimately their responsibility for accuracy and quality. Someone on a professional surveyor’s field crew, or office staff could be considered directly under their responsible charge; would the same apply to a contracted service? Campbell has presented on this subject and has interacted with professional associations and boards of registration.

One way of looking at this is “Who is ultimately responsible?” For example, a professional surveyor establishes control, sets GCPs, chooses an appropriate sensor payload, plans the flight height and speed to meet the accuracy requirements of the project, and flies the site. This all requires the professional judgment and skills of the surveyor. Unless the surveyor does all the processing themselves, they might have otherwise handed the data off to office staff, working under their direction. This is the step in the workflow that a processing service can fulfill. Provided that the surveyor performs the appropriate QA/QC steps, they maintain responsibility for the entire process.

“We do not want our customers to simply “trust” us,” said Campbell. “It needs to go beyond that. We urge customers to do quality checks. We are confident in our deliverables, but it needs to go beyond trust, to verification.”

“Do we use, for example, algorithms to try and intelligently classify ground versus nonground objects? Absolutely, we do. And then we have humans go through to run QA, run analyses, and make sure it’s good,” said Campbell. “Some projects might require minimal supervision and changes if it’s a relatively smooth dirt site that has nice clean contours and no objects that might take a lot of human QA. Whereas sites with a lot of objects, vegetation, hills, slopes, rock features, and noise—might take a substantial amount of human intervention to get it working. So, we are huge proponents of a blended human in the workflow. We have humans at every step, checking the data and fixing it as necessary.”

Powerline classification and drafting from processed drone images. – Source: Aerotas

Independent verification is one of the central tenets of professional surveying. Aerotas processes a lot of ALTA (land tile survey) projects for customers and is familiar with how to meet those standards. Campbell notes that they have built a lot of their QA/QC processes around meeting standards like the ASPRS (America Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing). “The society is made up of professional photogrammetrists, and they have produced rigorous standards, specifically about aerial surveying accuracy. As someone with statistical roots, this speaks to me.” Aerotas provides customers with reports that help them, together with their own ground truthing, determine if standards are met.

Ultimately, the decision to use a drone processing service should be about the optimal use of resources. Are you a large firm with enough projects to have the software and experienced staff to do all of the processing in-house? With present skills shortages, this can be a challenge for even the largest firms. Or are you a smaller firm that could use a helping hand? If all steps of the workflow are handled with skill and diligence, using a processing service could make even the smallest firm more competitive in the market for drone mapping and surveying.